The Early Recording Industry and His Master’s Voice

In The Mending, Douglas Thompson presents his sister Jane with a record for her birthday. It is 1916. He was pleased that the record, which he had purchased at the local drug store, cost only 85 cents—a discount of 15 cents from the usual retail price. Afterwards, the family played the record on their phonograph.

How common was it for families to own phonographs in 1916? The Thompsons were, at this period of time, fairly well off. Did one have to be well off to own a phonograph? Apparently, not. By 1920, most families in North America had a phonograph (or record player). In 1910 alone, 30 million records were sold. The number continued to increase, including during the war years, when patriotic songs were popular. The unifying effect of those patriotic songs was not matched, however in the industry that sold the records from which those songs were played.

From the earliest of times (and still today ) the recording industry was highly competitive with revenues being spurred or hindered through marketing campaigns and lawsuit principally waged in the early 1900s by three companies: Colombia Phonograph Company, the Victor Talking Machine Company and Edison Bell Phonograph Corporation.

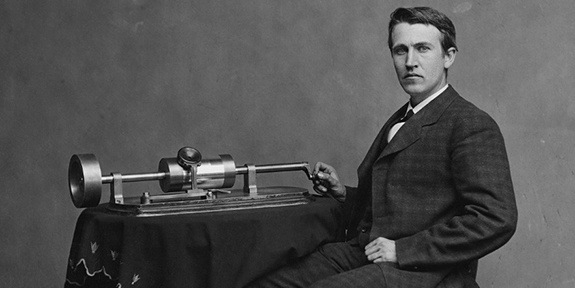

The phonograph itself was invented by Thomas Edison, the prolific creator who in his 84 years acquired almost 1100 patents. In addition to inventing the incandescent lightbulb, for which he may most often be remembered, he also invented the moving picture camera and the phonograph and he improved other inventions including the telephone and telegraph.

With the phonograph invented in 1877, Edison also invented the first type of sound recording device. His was in the shape of a cylinder from which the sound emanated when played on the phonograph. The cylinders were stored within cardboard canisters (from which came the expression “canned music”). Edison hoped that his cylindrical recording system would be standard for the industry.

The cylinders

However, Edison would not tolerate others who sought to emulate his system. Worn down by constant litigation, his competitors sought a different mode of recording sound and devised the flat disc initially made of shellac (a forerunner of vinyl) in a shape, if not a size, with that which we are familiar.

The flat disc records were easier to store than Edison’s canisters and less susceptible to rolling off a surface and breaking in their fall. Flat discs eventually became the industry standard. In 1913 Edison too switched to the flat disc though he continued utilize grooves that went up and down instead of side-to-side as was the case for the other flat discs. This meant that those who bought Edison’s records had to buy his phonograph. The prevalence of other phonographs that could play the flat disc offered by his competitors, ultimately edged Edison out of the recording industry. In 1930 his company stopped producing records at all.

But until that time the three dominant players in the industry continued to battle it out. The disputes were not limited to those with Edison. For a time, a record (whether cylinder or flat disc) could only hold one song. There was no side A and side B. But by 1904 Victor had devised a way to capture sound on both sides of the surface. Naturally, Victor obtained a patent and attempted to prevent others from producing two sided records. After a number of court battles, Victor resiled from its position and two sided records became the norm.

Edison and Victor had another interesting encounter—although this one did not end in a lawsuit between them. In the 1890s, an English artist named Francis Barraud inherited from his brother-in-law an Edison phonograph, a number of cylinders and a dog named Nipper. In 1898, he painted the three together, with the dog listening to the phonograph. He then offered the panting to the Edison company. It was declined by the Edison manager on the basis that “dogs don’t listen to phonographs”.

While that might be true, the rejection may have had as much to do with the Edison company view of marketing. The first images that appeared on the Edison canisters were not of cute animals, or of the phonograph itself. It was not of the artists whose music was captured within the cylinder inside the cannister. The first images on the cannister were of a scowling Edison. The text contained copyright and patent warnings. Only in smaller text was there any mention of the music within. At that time at least, it seems that Edison was more interested in preventing infringement than in promoting sales.

Having been rejected by the Edison company, the artists Barraud amended his work, painting over the Edison products and replacing them with those of the Victor company’s British affiliate, the Gramophone Co. of Maiden Lane. In it 1901 happily purchased the painting for £100. The image, titled “His Master’s Voice” (later HMV) became one of the most iconic trade mark images of the industry.

A final word. The original flat disc records could only hold four or five minutes worth of music per side. Even with two sides to a record, one needed a number of records to have all of the music of a particular opera or a ballet. To sell them together, they needed to be cased somehow. In looking for the solution, the German record company Odeon, took its lead from the photograph—and photo albums. They created phono albums, or record albums in 1904 for their release of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite.

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series