From Serialization to Audible – The Evolution of Reading Fiction

By Colleen Mahoney

I love audiobooks, especially the distraction they offer while doing chores…or on a long road trip. My sister and I recently listened to Tom Hanks (brilliant as always) bring Ann Patchett’s masterpiece “The Dutch House” to life, on a road trip between Toronto and Calgary. The miles flew by.

My assignment is to deliver a brief history of reading…and in reading fiction. But that at least offers a short cut, as reading on its own could take us all the way back to 3500 BCE! Instead, we’re going to move straight past the ancient Sumerians (who developed a rudimentary alphabet) and Gutenberg (who invented the printing press) all the way to the 18th century – when the novel, as a genre, took form…and the 19th when it really took off in popularity.

The Novel

PressBooks (a publishing platform for educators), attributes the rise of the novel to three societal changes:

1. Technological advances in the printing press which made books more affordable and readily available.

2. Increases in literacy rates among working-class men and women leading to more demand for books.

3. And…the fact that authors became dependent on these new reader groups for success and therefore, wrote books they knew would be popular.

So, what would these new readers like? The answer is…stories that they could relate to, featuring middle class characters, or times and places that were familiar. A couple of examples:

- The Soldier’s Wife by G.M.W. Reynolds [1853] is a novel about love and war, set during the Napoleonic era. The story follows the lives of several characters, including a soldier and his wife, as they navigate the turbulent political and social landscape of the time.

- Guy Mannering by Sir Walter Scott [1815] is a tale set in late 18th century Scotland and follows a one-time astrologer who becomes involved in a series of adventures while meeting a vibrant mix of characters from the everyday to the exotic.

While these books may have been more relatable, readers did not lose their appetite for high adventure or the supernatural. A first-rate adventure story, like Treasure Island (Robert Louis Stevenson), a dark tale like Dracula (Bram Stoker) or a gripping detective novel like A Study in Scarlett (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) certainly had people talking and buying.

The novel was believed to have its roots in French romance and many thought they were incompatible with English values. For women, in particular, reading novels was frowned upon, because females were perceived to be easily influenced by books about love and romance and could be led by them to engage in immoral activities.

Serialization

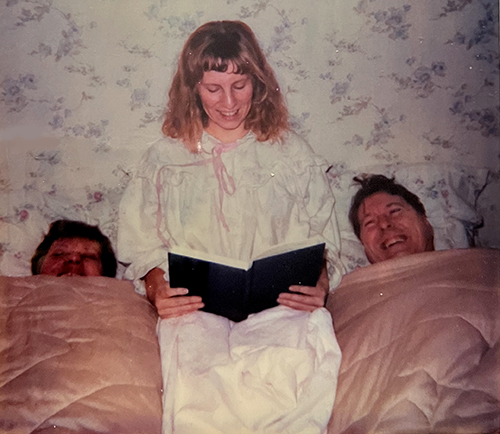

A book was still a luxury that was out of reach for most of the working class in the 18th and 19th centuries. To remedy this, and meet the demand of new readers, newspapers and magazine publishers started printing books in serial form – a much more affordable option. In addition to reaching a larger audience, a publisher could determine the popularity of a story by how many copies it sold. If popular, it would be bound into book format and fetch a greater price. Writers benefited from the steady monthly income, with the added benefit that it grew their fan base. The serialized novel was read then in much the same way a television series is watched now (unless you “binge”). Suspense grows with each installment, until the dramatic conclusion is reached. It was often the case that the regular installment was read aloud by one family member to the others (like an audiobook today).

Serialization began in the 1700’s, but did not really take off until The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (Charles Dickens) was published in 19 installments from 1836 to 1837. In the US, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Harriet Beecher Stowe) was published over a 40-week period starting in 1851, in an abolitionist paper called The National Era. This tradition continued into the 20th century. F. Scott Fitzgerald published Tender is the Night in four installments in Scribner’s Magazine in 1934. Agatha Christie, published many of her novels in The Strand Magazine between 1932 and 1944. In France, Alexandre Dumas was the master of the serial, publishing both The Count of Monte Christo and The Three Musketeers this way.

Agatha Christie’s The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920) was published in paperback in 1935.

Over time this practice became so prevalent that most “quality” writers published in serial format and “second-rate” writers were forced to publish in book format. The downside for the author was that he or she had a hard deadline to meet – the public demanded its next installment. If you couldn’t keep up with demand, the newspaper or magazine would drop you from its stable of writers.

Penny editions, serialized stories of 8 to 10 pages, published weekly (and costing a penny), became wildly popular in the 19th century in the UK. These were less expensive than serials for Charles Dickens’ works (his installments cost 12 pence each). Typically, penny editions were aimed at young working-class men and they evolved into more sensational stories featuring the exploits of detectives or criminals. In North America, the equivalent was “dime-store novels” like Sweeney Todd – going for 5 or 10 cents.

I now know why my mother referred to me as Mother Hubbard when I padded downstairs for hot porridge on cold winter mornings.

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series