The Evolution of Ready-Made-Wear

In reviewing 1907 editions of The Conservator, the local Brampton paper, I was struck by the extent of men’s smoking coats, overcoats and even suits advertised for sale. By contrast, ladies were offered pre-measured wool and silk fabric available in waist lengths, dress lengths, and blouse lengths—presumably being the yardage required to make a standard skirt, dress or blouse. Some material was striped; some came with silk embroidered spots. It seemed that ready-made-wear – clothes available “off the rack” – were then available for purchase in Brampton by men but not women. What, I wondered was the evolution of the ready-made-wear industry.

Not all that new

It turns out that the notion of ready-to-wear clothing was not all that new. Military uniforms, for example, were produced in workshops in ancient Roman times and prior to that merchants in Babylonia were making and distributing some garments that were ready-to-wear.

By the second half of the 16th century, gloves, stockings, shoes and hats were being mass produced and available for purchase off the peg, as it was sometimes called. In addition, collars and sleeves were being manufactured for use by those making bespoke shirts, blouses and dresses.

But for the most part, clothing continued to be made to measure either by a tailor or a seamstress or at home by a family member or a family servant. Garments once made would last for years—sometimes a lifetime—though they were often altered to suit the style of the day. For example, collars would be made wider or narrower or rows of lace would be added or removed from sleeves.

Change in Menswear

This all began to change in the early 1800s. Repeating history, in 1812 the U.S. government mass produced military uniforms. The successful example of this program, combined with the revolution in weaving and clothing production processes and, later, the invention of the sewing machine, led to the creation of a ready-to-wear clothing industry for men. As the century advanced, the fashion style for men evolved to one less ornamental, involving plainer fabrics and including loose fitting trousers rather than form fitting pantaloons. Whether this change in fashion was caused by the emergence of the ready-to-wear industry is not clear. But as will be seen below, the change in fashion certainly aided the evolution of the industry.

Change in Womenswear

It took longer for women’s clothing to be manufactured on such a large scale. The reason relates in part to the clothing style of the 1800s described by Colleen in her article about the Rational Dress Society. For all of the 1800s and for the first decade or so of the 1900s women’s clothing was highly decorated and most importantly, form fitting. Had the style changed to the simpler, straighter, loose fitting styles of the Roaring Twenties earlier, the ready-to-wear industry for women’s clothing may have come on stronger sooner. But that is not to say it did not come on at all prior to that time. The advent of large department stores like Eaton’s and Simpsons in Canada or Marshall Field and Macy’s in the U.S. and the mail order catalogue businesses that they spawned–endeavours that required large amounts of products for retail consumption--meant that even before the Roaring Twenties some ready-to-wear clothing for women was available. (See our Eaton’s Christmas article on the evolution of department stores and catalogues.)

Sizing

The importance of the loose fitting nature of the female dresses and the male pants is this: the promise of ready-to-wear garments is that they are to be just that, ready to wear. Once purchased, no alteration or very little alteration is to be required. Loose fitting clothing can “fit” two different wearers equally well even if the wearers have different body shapes and measurements. This is not true with form fitting pantaloons or for the most part, the hour glass dress--although a good corset could help some.

In fact, the sizing issues created real problems for the mail order catalogue industry: for both women purchasing, and vendors selling, female garments. For a man, the measurement of his chest was a good indicator of the size of jacket and shirt he would require. With those items and the pants sold as separates, the ordered male clothing was likely to fit or to fit with some minor alterations.

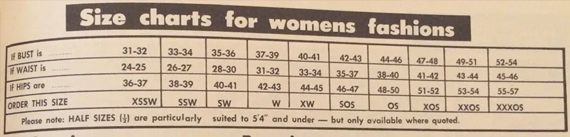

The same was not true for women, particularly for women ordering dresses. Women with the same bust measurement could have very different body shapes. The frustration for both women and catalogue sales companies resulting from the frequent return of merchandise led the U.S. government to create a process for determining standard sizes of women. Between 1939 and 1940, 14,698 U.S. women were measured in over 50 ways. Data was collected regarding, among other things, their weight, height, the usual girths (i.e. bust, waist and hip) and some other girths as well (e.g. ankle and knee).

Based on the recommendation that the sizes be numerical, like shoe sizes, eventually a number of sizes were determined. Manufacturers were then urged to produce clothing in even sizes only in order to reduce production expenses. Thus women became familiar with sizes like 8, 10, 12, 14, etc. There were options to the standard sizes too including Misses (for slender, fully formed women, with petite (short) or tall options) and Women’s (for those with more exaggerated curves again in tall or shorter options).

The system wasn’t perfect. This was in part because by the time the sizes came into use in the late 1950s, twenty years had passed from the gathering of the data. Fewer women at that time and even less since held the hour glass figure of those measured in 1939 and 1940.

Further, the measurements were based only on data collected from white women. In 1970, the commercial standards were updated but at that point they became voluntary. Retailers realizing that women felt better about themselves in purchasing smaller sizes, ceased to use the new standards, adopting instead “vanity sizing” with sizes as low as zero.

Consequences

The explosion of the ready-to-wear clothing industry had many positive effects. It accelerated the transformation of women’s clothing style, realizing the objectives of Lady Harberton and The Rational Dress Society described in Colleen’s article. Because the clothes were mass produced with thinner fabrics and without so many embellishments, it lowered the price of clothing. This was particularly helpful in an era where magazines showing new fashion styles proliferated (See Ask Colleen: Reading in the first decades of the 20th Century from our April 2022 newsletter) and where, in a growing economy, there was no shame in purchasing goods beyond those that were strictly required. The trend was also said to have reduced the differences between the fashion styles of those of various classes or family income levels.

But the changes were not welcome by the many tailors and seamstresses who had formerly made their living producing bespoke clothing, often in their own homes. They and their champions argued that the movement would result in everyone being dressed identically. They could not have foreseen the incredible amount of ready-to wear clothing that would be produced--enough so that one only very rarely, as my mother would say, see oneself walking towards oneself on the street.

Neither the early opponents nor the supporters of the ready-to-wear clothing industry could have foreseen the size of closets that would one day become standard in homes to hold the vast numbers of garments acquired. They could not have foreseen a time where a garment would be worn once, twice or three times only; where the processing and production of textiles would account for 20% of global water pollution or 10% of global carbon emissions; or where the production, distribution and sale of clothing would constitute the fourth largest manufacturing business in the world.

For more on the above see these two good articles:

Seamwork, by Katrina for an article on the History of Clothing Sizes Posted in: Creativity & Mindset, Style & Wardrobe • December 31, 2015, https://www.seamwork.com/articles/the-origins-of-clothing-sizes

Ready-to-Wear: A Short History of the Garment Industry by Dolores Monet •May 2, 2022 https://bellatory.com/fashion-industry/Ready-to-Wear-A-Short-History-of-the-Garment-Industry

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series