Will Kissing be Prohibited? Potions, Elixirs and Drugs

“Will kissing be prohibited?” the December 19, 1907 headline read. Perusing past issues of The Conservator, Brampton’s local paper of the last century, was a big part of the research process in the writing of my Beneath the Alders series. A lot of headlines caught my eye, but this one above a 10-inch article nestled between columns of the serial novel, Written in Red, Chapter IV, really stood out.

The article reported on a movement among certain scientists to ban the “Osculatory process” of kissing, which was viewed as a means of spreading gripe, scarlet fever, measles, mumps, whooping cough, typhoid fever, diphtheria, meningitis, tuberculosis and many infectious skin diseases including erysipelas. Presumably, the spread of skin diseases was accomplished by other parts of the body coming together in the act of kissing—rather than the kissing itself. Of course, I am thinking of hands on faces, etc. (You don’t think I was going further than that do you? And if you are wondering where you heard the word erysipelas before, think back to Season 1 of Downtown Abbey and the disagreement between Mrs. Crawley and the Dowager Duchess as to the cause of the rash on the hands of Mr. Mosely.)

The early 20th century scientists recommended that notices of the dangers of kissing be posted in railway stations, on street cars and in other public places. They conceded that there would be no point posting the notices in cozy corners, porches, shady nooks or moonlit lawns. The article did not say whether the futility in such signage arose from the poor lighting in those venues (which would render the notices illegible) or the advanced stages of amorous pursuits within such locations (rendering impossible the ability to forestall Osculatory activity). I rather suspect it was the latter.

Recognizing that the public notices would not entirely curtail the “swapping of spit”, as my father sometimes refers to a smooch, or the even the less saliva interchanging act of kissing innocent babies, (who were said to be particularly subject to infection), the advocates also proposed legislation compelling the disinfection of the mouth and the purification of the breath.

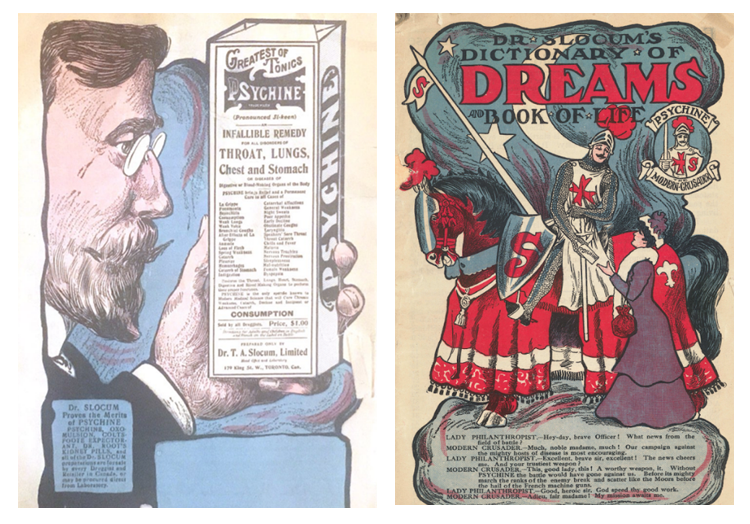

Up until that point in the article, I assumed it to be a genuine report of a real –though ludicrous-- public health movement of the times. But then the article took a turn, for the unnamed reporter next described the very elixir required for such disinfection and purification: Psychine (pronounced Si-keen), a triumph of the medical world!

Available from all druggists in $.50 and $1.00 quantities or directly from Dr. T. A. Slocum, Limited, 179 King Street West, Toronto, it was “the greatest and most effective purifier and germ destroyer known to medical science for the mouth, throat and breath, as well as for the blood, stomach and lungs.” It was gaining attention world-wide.

As proof, the article offered the testimony of Mrs. Lizzie Garside, 519 Bathurst St., London, Ontario. She wrote as follows:

Dear Dr. Slocum Co,

I am sending you photo [sic] and testimonial herewith for your great remedy Psychine. Your remedies did wonders for me. I was about 28 or 30 years of age when I took Psychine. The doctors had given me up as an incurable consumptive. My lungs and every organ of the body were terribly diseased and wasted. Friends and neighbours thought I’d never get better. But Psychine saved me. My lungs have never bothered me since, and Psychine is a permanent cure.

For a couple of reasons, I found it interesting that the letter was addressed to “Dr. Slocum Co”. First, it indicated that back in the day, Ontario physicians were able to incorporate, something that was later prohibited although it is now permitted to a limited extent. Secondly, who would address a letter of this nature to a physician and include evidence of his liability limiting incorporated status (the “Co” at the end)? Possibly only the purported recipient. But I digress.

At that point, I realized that the article was not a news report but was in fact an advertisement—cleverer possibly than the advertisements for other cure-alls and potions in that same issue of The Conservator which were transparently the advertisements they claimed to be.

Suffering from rheumatism? Try the South American Rheumatic Cure which permanently eradicates the last vestige of the disease from your system. Sold by John Hodgson – 74

Do you wake each morning with stomach trouble, a headache and a bad taste in the mouth? Try a stiff dose of Nerviline with some sugar in a tumbler of water. Nerviline invigorates, braces, tones and puts vim and snap into your movements. You’ll feel tiptop in a few minutes and be fitted for a hard day’s work. Large bottles available everywhere for just 25 cents.

In pain with sciatica? The inflammation of the sciatic nerve, the largest nerve in the body? The pain, apparently, is the cry of the nerves for richer, redder blood. The answer is to treat the blood and rebuild the nervous system. This can be promptly done with Ferrozone which is “absolutely sure to cure”. Boxes sold by all druggists—for 50 cents apiece.

I am not sure what stomach trouble was intended to be addressed by Nerviline or whether it proved successful but given the number of Canadians who continue to suffer from rheumatism, sciatica and the many illnesses said to be addressed by Psychine, we can be sure that the relief offered by South American Rheumatic Cure, Ferrozone and Psychine was neither permanent nor absolute.

However at a time when true remedies were not available, consumers cannot be faulted for trying those on offer even if the cost was dear. Applying inflation, that $1.00 quantity of Psychine would cost just less than $30.00 today.

In 1920 and again in 1927, the Canadian government did pass legislation affecting Psychine. It was not of the nature proposed by those concerned about the disease spread by kissing. Intending to protect the public from expenditures on drugs with very little correlation to the claims made about them, the government enacted the Food and Drugs Act. Among other things, the Act outlawed the making of false or exaggerated claims by manufacturers and retailers of drugs and foods. Laws today prohibit the advertisement of any drug in a manner that is false, misleading or deceptive or is likely to create an erroneous impression regarding its character, value, quality, composition, merit or safety. (Fun Canadian fact: the 1927 version of the Act also included a separate section prohibiting the sale of products that resemble or imitate maple sugar or maple syrup.)

The Psychine article in The Conservator, was indeed a cleverly placed advertisement. But did the movement –the movement to ban kissing described within it—exist? It did! Read the Ask Colleen article in this Newsletter, to learn more.

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series