While I did all of the initial research for my Beneath the Alders series and for the first book in the series, The Innocent, I was greatly assisted in completing The Beleaguered and The Mending by the research skills of my good friend Colleen Mahoney, a pre-maturely retired librarian. For this newsletter, I asked Colleen one question only: what can you tell us about the Christmas Truce of 1914? Her poignant response is below.

When we think of the First World War, we think of an unspeakably, long and bitter conflict punctuated by massive and horrific battles which took the lives of a staggering number of souls, both military and civilian. We think of trenches, mud, cold and the accompanying diseases that came with exposure to the elements for weeks and months on end. We also think of guns and mortars of a size and explosive force never experienced before. And, we think of poison gas…

But in the midst of all that, an extraordinary event took place on Christmas Day of 1914, in which men on both sides of the conflict came together to exchange wishes of peace and good will. So, what proceeded this event and how did it come about? This is the story of the Christmas Truce of 1914.

The autumn of 1914 had seen unprecedented warfare. As the powerful German army attempted to push its way through Belgium and into France, a concerted effort was made by the Allies to keep them from reaching the Channel port towns where they could potentially cut off the Allies’ supply and communications lines from Britain. “The race to the sea” as it later became known, gave rise to many costly battles including the Battles of Aisne, Ypres, Yser and Bassee.

While the Germans made substantial advances toward the sea, the Allies held and the two opposing forces eventually became entrenched along a line that stretched from the Swiss border to the North Sea. By October 18, the “Western Front” as it became known, was complete and the two sides were at a virtual standstill. No longer able to outflank one another, their only option was a frontal assault in an attempt to break through enemy lines. The last major frontal assault of 1914 was on December 19. It was a battle fought in the freezing rain and which culminated in many thousands of dead and wounded - and no strategic advantage for either side. The German and Allied troops were exhausted, demoralized, and horribly cold with many suffering from frostbite.

At this point, I should explain that as the Front began to form, Allied and German soldiers alike, began to dig shallow holes in which they could crouch to protect themselves while exchanging fire with the enemy. Over time, these holes grew deeper and wider and soon they began to merge with other holes along the line, forming trenches. As time went on, and it became obvious to all that the trenches were going to be relatively permanent structures, they became more sophisticated. They were then strategically placed and reinforced with sandbags, wooden beams and wood flooring. Embankments were built at the top, facing the enemy and fortified with barbed wire fences. Soldiers would spend from four days to two weeks in these trenches, until they were rotated out for rest or support duties.

The trenches of the opposing armies were situated anywhere from thirty to several hundred yards from one another. The area between the two trenches was known as “no man’s land”. It was littered with tree stumps, mortar shells and craters, barbed wire and, unfortunately, the many bodies of the fallen. It was an odd existence, in that, while the soldiers could not see one another, they were often close enough to hear one another talk and smell the meals being cooked. In fact, there was quite a bit of banter exchanged across no man’s land (many Germans had lived in England before the war and could speak and understand English).

The rains were unrelenting that Fall and into December. The trenches were swamped and no man’s land became a quagmire. Conditions were equally wretched on both sides. It looked as though it was going to be a very bleak Christmas indeed for those unlucky enough to be in the trenches during that week. While you could hardly blame them for feeling down about their situation, the soldiers would have been cheered to know that they were very much in the hearts and minds of those back home.

When it became apparent that the war would not be over by Christmas, as many had hoped, Princess Mary (aged 17), daughter of King George, became concerned about the morale of the soldiers and sailors who would be spending the holidays in the cold and wet of the front lines instead of in the comfort and warmth of their family homes. She decided that a Christmas gift from the nation would be a thoughtful way to show appreciation for the many sacrifices they had made. She began a very successful public campaign to raise funds for the gifts.

The gifts took the form of small embossed brass boxes that became known as Princess Mary’s Tins (her portrait and initials were embossed on the lid). The contents of the boxes varied to suit the needs of the men and women receiving them. For instance, smokers received tobacco, cigarettes and a tinder lighter, while non-smokers received a khaki writing kit with paper and a pencil and acid tablets. Indian service men received sweets and spices and nurses received chocolate. All boxes contained a greeting card with wishes of Merry Christmas and a Victorious New Year and a photograph of Princess Mary. Nearly half a million tins were distributed by Christmas Day.

In addition to Princess Mary’s campaign, many British businesses began to manufacture speciality items for Britons to send to their loved ones on the front. For instance, Con Amore branded cigarettes began making cigarettes whose slogan was, “In the Trench, Mess, Billet or on Shipboard, every smoke will remind him of you – the giver”. The cigarettes were embossed with regimental crests. Christmas puddings, footballs, books and correspondence cases were sent to the continent in bulk.

Similarly in Germany, Kaiser Wilhelm II is said to have sent his troops a kit that contained a pipe bearing his likeness with an accompanying pouch of tobacco and Tannenbaum (Christmas trees) in an effort to bring some cheer to the troops. The Germans also received gifts from home which included things such as sausages, cognac, warms clothes and chocolates.

Needless to say, while the troops on either side of the front may have been exhausted, cold and demoralized, they were unusually well provisioned leading up to Christmas Day.

There was no formal truce called for Christmas Day despite the fact that Pope Benedict had lobbied for one (he had been turned down by both sides). Regardless of this, rather spontaneously, on Christmas Eve, a temporary, simultaneous and sporadic peace broke out up and down the front line. (It is true that some sectors continued to volley shots across no man’s land that day but there were no serious battles anywhere along the front.) In some sectors, the peace lasted a day and, in at least one sector, fighting did not resume until New Year’s Eve. It is estimated that about two thirds of the troops, or 100,000 men, took part. While some French and Belgians were have said to have participated in the truce, they were less keen, as it was their lands the Germans were occupying.

Thus, on the afternoon of Christmas Eve, the unrelenting rains came to a stop, the trenches drained and the temperatures dropped. The cold was somewhat of a blessing as the muck and mire hardened and made movement easier. The gunfire dwindled and, in some places, stopped altogether. Many noted that they could hear bird song for the first time in months.

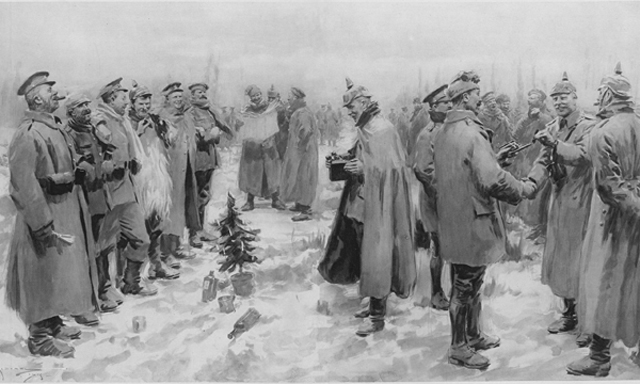

As German’s celebrate the holiday on Christmas Eve itself, the first thing many soldiers reported seeing were the little Christmas trees - lit with candles - being erected on the German embankments. This was usually accompanied by the singing of carols. The English responded by singing carols louder - and when both sides were familiar with the same carol, they sang together in their respective languages.

In some sectors, officers actually agreed to a ceasefire, while in other places it was the infantry men themselves who made informal arrangements. And in some places, there was merely a call across no man’s land – “you no shoot, we no shoot” and the soldiers cautiously rose out of the trenches and stepped into no man’s land. For many, it was the first time they clearly saw their opponents.

The first order of business was to collect the dead or dying left in no man’s land and it was reported, they often prayed together over the bodies. Once this act of mercy was completed a celebration of sorts ensued. Friendly banter was traded. Many photos were taken. Meals and drinks were shared. Gifts were exchanged. And if fact, many of the gifts described above ended up in the hands of the “enemy”. There are a few accounts of a football appearing and an informal “kickabout” ensuing. In one account, a German barber who had been living in London, gave one of his former English customers a haircut and then carried on giving others cuts as well. Another German gave an Englishman a letter for his sweetheart back in Manchester. Names and addresses were exchanged. As the truce drew to a close, they shook hands and retreated to their respective trenches.

By all accounts, it was a beautiful reminder to all who participated that, despite the brutality of the previous months, they were all just men with more in common than not. It remains difficult to understand how, after this extraordinary show of goodwill, these men then simply went back to shooting at one another.

There are some rather cynical views on this. Some have argued that the men who took part in that early stage of the war were drawn from the regular British, French, Belgian and German armies. They were hard-bitten professionals: war their business and fighting their job. They had nothing personal against the enemy. By the time Christmas rolled around, they were exhausted and needed a couple of days off. An official break wasn’t being offered, but they saw the opportunity for one and they took it, knowing full well that it was temporary, and it would be business as usual soon enough.

And yet, in reading personal accounts of the Christmas Truce, it becomes evident that these hard-bitten professionals themselves were astonished at the events of the truce and truly felt blessed to be part of something both so utterly unexpected and so completely life affirming.

The Christmas Truce was never repeated again on the same scale. Commanders explicitly prohibited any fraternization - afraid it would weaken the resolve of the troops. However, in 1915, the artillery again fell silent and men were able to walk freely on their side of no man’s land with no fear of being shot. So, in this regard, the spirit of the Christmas Truce of 1914 lived on a bit longer. But as the war dragged on, obviously goodwill was exhausted. There was no equivalent pause in the last two horrific winters of that awful War which only ended on Armistice Day in November of 1918. Only a few weeks before Christmas.

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series