While I did all of the initial research for my Beneath the Alders series and for the first book in the series, The Innocent, I was greatly assisted in completing The Beleaguered and The Mending by the research skills of my good friend Colleen Mahoney, a pre-maturely retired librarian. For this newsletter, I asked Colleen questions about the history of lingerie.

Lynne: Judging by the increase in advertisements touting lingerie and the displays of sexy undergarments (usually red in colour) in lingerie shop windows, I surmise that February is a big month for the purchase of lingerie. It got me to wondering (as I do) about the history of lingerie. Is it a word that Francis Perry would have used when assembling her wedding trousseau in 1889 or that her daughter Jessie Roberts would have used when packing her European traveling trunk in 1926? What is the history of the word “lingerie”?

Colleen: The term “lingerie”, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), comes from the French word for linen and refers to the making or selling of linen cloth as well as all the articles of linen, lace, etc. in a woman’s wardrobe or trousseau. According to another source, the word being used in reference to undergarments specifically, was introduced in 1835 but did not come into widespread use until 1852.

However, the OED is British and leans towards European usage so I was still not sure how widespread its use was in Canada. To find out, I did a quick scan of The Globe newspaper (Globe and Mail today) for any mention of the term “lingerie” with a date range of 1880-to-1939 to see how often the term was used. This is what I found:

Globe and Mail – frequency of the term “lingerie” in both newspaper ads and articles

1880 – 1889 – 14 times

1890 – 1899 – 47 times

1900 – 1909 - 577 times

1910 – 1919 – 2422 times

1920 – 1929 – 1982 times

1930 – 1939 – 1794 times

The vast majority of the “hits”, as you can imagine, were retail advertisements placed by companies like the T.E. Eaton store and Robert Simpson Co. and they were, almost exclusively, using it in reference to women’s undergarments. When the term was mentioned in a newspaper article, it was most often when reporting on a society wedding and was referring to the bride’s trousseau. From this I would deduce that its possible Francis may have used the term in 1889. And because of the frequency with which the term was being used in media advertising between 1920 and 1939, it is very likely Jessie would have used the term when packing for Europe.

I found it interesting that the frequency of the term’s use in the newspaper rose and then fell over the years. Apparently, underwear sales fall off fast during economic hard times. It makes sense when you think about it though…underwear, by definition is worn under other clothes and therefore is not seen by the public (although that has perhaps changed a bit over the past couple of decades). While essential, one can “make do” with less than impeccable underwear when money is tight. The decline in advertising usage frequency in times of economic challenges fits nicely with what we know about the economic history of the period – North America experienced an economic depression in the mid 1880’s that lasted until the mid 1890’s, and of course, the 1920’s was the decade which ended in the Great Depression that began with a terrible market crash in 1929.

Lynne: So lingerie is a word for underclothes and in the time period we are talking about, maybe particularly “fancy” underclothes given its use in relation to trousseaus. Last year you wrote a great article about changes in women’s fashions, including a movement to make women’s clothing less restrictive. Click for article. You said that women were thoroughly trussed up well into the Victorian Era (1839 – 1901) with an attire that typically consisted of corsets, stays, petticoats, bustles, heavy skirts, long sleeves, and tight collars. In reading your article and in reading books written about those earlier times, we come across those words but some of them are hard to picture. What are these things?

Colleen: I found that the definitions or descriptions of these different pieces often differed, sometimes wildly, according to the source. For consistency, I decided to again use the trusty OED to provide clarity on what these garments were and their intended uses. Quite honestly, corsets, bodices and stays all sounded like the same thing with different labels to me, so I had to dig a little deeper. According to The Dreamstress, a website devoted to “sewing, history and style”, “stays” pre-dated the “corset” and were “worn to turn the torso into a stiff, inverted cone, raising and supporting the bust, and providing a solid foundation on which the garments draped”. These were popular during the 17th and 18th centuries.

The corset arrived in England from France in the late 18th century and was described as being boneless and as a result much less constricting than stays, and softer, as they were normally covered in quilted material. However, time elapsed, fashions changed and alas, whale bones were once again added, and the body cinched tighter so in this later period corsets might as well have been stays and indeed the terms were often used interchangeably.

Bodices, according to The Dreamstress, date back to Tudor times and were also originally a garment for the upper body and also stiffened with bones – but may or may not have had sleeves.

“Bustles” and “petticoats” proved to be far more straightforward and I have provided the OED definitions below.

Petticoat: a garment worn by women or girls and young children (perh. orig. a kind of tunic or chemise, but) usually a skirt dependent from the waist. A skirt as distinguished from a bodice worn either externally or beneath the gown or frock as part of the costume and trimmed or ornamented; an outer, upper or show petticoat. An underskirt of calico, flannel, or other material. The skirt of a women’s riding-habit.

Bustle: a stuffed pad or cushion, or small wire framework, worn beneath the skirt of a women’s dress, for the purpose of expanding and supporting it behind; “dress-improver”.

Lynne: Where did the brassiere fit in? Did it compliment the corset or perhaps, replace it?

Colleen: Brassieres for the most part replaced the corset. The brassiere, interestingly, came about as part of a push in the 19th century to improve the health of the general population and women in particular. It likely didn’t hurt that at that time an increased number of women were entering the medical field either as nurses or as doctors. They were likely more attuned to the drawback and hazards of corsets, i.e. their impeding the proper functioning of some organs as they were too constricting and did not lend themselves to women comfortably participating in physical exercise.

But abandoning the corset then led to the question of how to support the breasts without whalebones forcing them up from below? The answer, of course, was to support them from above using the shoulders and…just like that, the bra was invented! One of the very early patents for a brassiere was issued to L.L. Chapman in 1863, in which it was described as an “uninjurious bust support”.

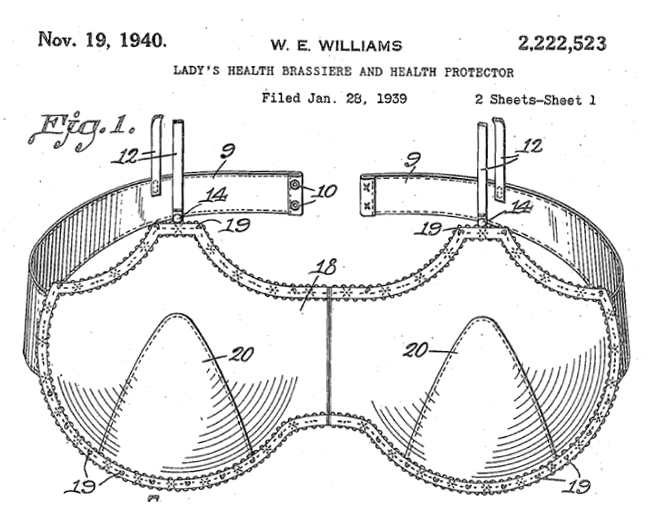

Interestingly, sports bras were patented in the early 1900s. Ethel M. Quirk introduced the “bust support for exercise and maternity” in 1917, while Daniel J. Kennedy was issued a patent for “breast protector for athletics” in 1929. Many other brassieres patented within this period include those: for smaller or larger busts, promising to be comfortable, or attractive, or providing free respiration, or for stout figures, or specifically for women after mastectomies. My favourite was the patent issued to Walter Emmet Williams in 1940 for a massaging, deodorizing bust support using glass beads and pads soaked in a “suitable” chemical. If you’d like more information on this amazing bra, click on the image below to go to the full patent.

Lynne: Last year when I was visiting Kensington Palace I picked up a book that described court life. In the mid 1700’s when women wore mantua dresses -- the form-fitting boddices and the whale bone hoop extended skirts that would cover a small table—they relieved themselves while standing and fully dressed by placing a gravy boat shaped bourdaloue under their skirts and clenching it between their thighs. There was no need to first pull down knickers as they had not yet been invented. When were knickers invented?

Colleen: While underpants weren’t common in the 1700’s there is some evidence that some women were wearing them as early as Renaissance times (15th and 16th century) to help with cleanliness, protect them from the cold and prevent their nether regions from being accidentally exposed, say in a fall. It is said that it also offered some protection from lecherous hands. They were however, and continued to be well into the 19th century, crotchless allowing for air circulation and for the woman to relieve herself (thus the bourdaloue) without having to remove all of the layers of clothing described above. As clothing became less restrictive, buttons would be added to the opening to provide some modesty, and then later sewn closed completely. But what goes around comes around, and some shapewear, like Spanx today, are designed with an opening to allow ease of using a toilet. I love the variety of names given to underpants including; drawers, knickers (derived from knickerbocker), smalls, britches, step-ins, panties, gitch (the term I was raised using), etc. The list goes on.

Lynne: When we see men in kilts, we are all a bit curious about whether they are wearing underwear but I suppose there was a time when no one did, it was just a little more likely that this would be revealed when the fabric was knee length and pleated. So did they or didn’t they?

Colleen: Men actually were wearing a type of underwear called braies as early as the Middle Ages. They looked a little like a loose pair of shorts – often made of linen, wool or even leather and tied at the waist and thighs. They had a front flap secured shut by button or a lace that could be opened when the man felt the call of nature. The purpose of the braies was to provide support, protect the man and his bits from chafing and protect his outer clothing from being soiled. Trews were similar to braies but were much longer.

There are many differing opinions as to whether Scots wore braies or trews under their kilts. The Word Wenches, a blog devoted to history says that generally the wrapped plaid (earliest style of kilt) was worn without braies, except in very cold weather. But the men were also known for pulling their long shirttail up between their legs and tucking it into their belts to form a sort of diaper. This totally makes sense to me.

However, another source I came across a few times says that yes, they likely wore something under their kilts (braies, trews or shirttail) until a Scottish military code from the 18th century itemized all the items that made up the uniform…but was silent on any kind of underwear. The soldiers took this as a challenge and grabbed the opportunity to wear nothing under the kilt. I’m not sure I buy this entirely…but it’s a good story. I did find references to trews being worn as part of the Highland Corps in 1793-1799 and the 71st Highland Light Infantry in 1807, but nothing referring to braies.

Today, kilts are normally only worn on formal occasions or for highland dancing and relatively few men own their own kilt. If needed, they rent them and it is considered bad form to “go commando” in a rented kilt.

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series