While I did all of the initial research for my Beneath the Alders series and for the first book in the series, The Innocent, I was greatly assisted in completing The Beleaguered and The Mending by the research skills of my good friend Colleen Mahoney, a pre-maturely retired librarian. For this newsletter, I asked Colleen a number of questions about the movement in the first decade of the 1900’s to “ban kissing” and some other related questions.

Lynne: Was the report in the December 19, 1907 issue of The Conservator –the report of the movement to ban kissing-- true?

Colleen: Yes, it actually was! At the turn of the 20 th century, many doctors and public health authorities campaigned to, if not outright ban kissing, at least strongly discourage it in certain cases.

A group of delegates at the International Congress on Tuberculosis, which took place in Paris in 1905, suggested a public campaign to reduce kissing which they described as “dangerous, detrimental and responsible for countless diseases”. Demonstrations were conducted in which many volunteers had their lips swabbed and the collected microbes examined. The test showed that the lips were swarming with bacteria - including those of tuberculosis (TB) and diphtheria.

In the same year you ask about and on the same continent, the Roanoke Times (February 1, 1907) reported that Dr. Somers, the Health Officer of Atlantic City, issued a health bulletin warning that kissing and influenza were closely linked, “and in view of the rapid spread of the grip (influenza) throughout the city, and in view of the known fact, that osculation, commonly described as kissing, is the most fruitful agent of the grip germ, it is advised that temperance and moderation in respect to (sic) the said practice be more generally observed”. As a result, the Chief Health inspector petitioned for money to have notices warning of the dangers of kissing printed and displayed in railway stations and other public places.

And the movement had legs. In Australia, as late as 1948, in response to high incidences of TB, public health physicians recommended a ban on kissing completely, though I did not find evidence that authorities ever implemented the recommendation.

Lynne: What prompted this movement?

Colleen: The incidences of outbreaks of diseases such as TB, diphtheria and scarlet fever grew significantly as the industrial revolution took hold in the 19 th century. Increasingly crowded cities and work places provided ideal breeding grounds for the rapid spread of contagions. TB was especially lethal – in 1900, 194 out of every 100,000 Americans died of TB, second only to influenza and pneumonia. In Canada, diphtheria was the leading cause of death for children under the age of 14 until the 1920s, with death rates hitting about 2,000 per year.

Surprisingly, until some significant medical advances were made in the late 19 th century, some of these illnesses were thought to be hereditary or congenital rather than contagious. (TB was one such example.) Once their contagious properties were discovered, health specialists sprang into action, looking for ways to prevent, stop spread and ultimately cure these diseases. Unfortunately, it would be decades before the discovery, and wide-spread use, of antibiotics came to pass and modern vaccines were only in the very early stages of development.

In the absence of any medical cure, avoiding close contact with individuals who had contracted a contagious disease seemed a very common-sense approach to stopping its spread. Many public health initiatives were put in place such as by-laws against spitting in public and legislation requiring that public houses have spittoons. Cleanliness was strongly encouraged in homes, especially in those that housed a sick patient. Housewives were encouraged to dust regularly with damp cloths and weirdly, to dampen the floor with wet tea leaves, all with the aim of keeping germs from being inhaled. The dishes, utensils and clothes of a sick person were to be sterilized and, if a patient died of the disease, their clothes and bedding were to be burnt. Drinking alcohol was discouraged because inebriation could cause careless sanitary behaviour. Sick people were advised to keep their distance when speaking and to cover their mouth when sneezing or coughing.

Discouraging kissing was a logical offshoot of all these actions. Parents were even discouraged from kissing their children. It was said that hundreds of “lovely, blooming children were kissed into their graves every year”. In one famous case of this, Princess Alice, a daughter of Queen Victoria, died from diphtheria in 1878. It was believed that one of her infected children passed it to her through a kiss. Newspaper stories at the time referred to it as a “kiss of death”. Paul Cuq, a French physician, published a journal article in 1904 warning that infants were particularly susceptible to contracting TB from kisses. He wrote, “Physicians should undertake a veritable crusade against the common habit of kissing children. The nicer they are, the more we smother them with kisses, without noticing that in our affectionate folly we might kiss the corner of the child’s mouth or even the whole mouth, thereby inoculating tuberculosis that we are carrying without knowing it”. In addition, Dr. Cuq pointed out “many young married couples have inoculated (with TB) each other by kissing on the lips”. Do you think he implying that old married couples don’t kiss on the lips?

Lynne: Did this movement persist? Was it prevalent?

Colleen: Well as you can see from the above examples, it certainly had its proponents. But it also had its detractors. Another French physician, Dr. Marabail, believed that it was almost impossible to prevent contagion, likening the attempt to try as you might “covering a field with a net in order to combat weeds… Let us continue to kiss each other: if kissing gives us a few extra microbes, we will forgive it, considering the sweet joys it brings.”

At the International Congress on TB (mentioned above), while there were a number of doctors advocating for a prohibition on kissing, there were many that believed that as a public health measure it was nonsense. The congress’s final report did not recommend a ban on kissing.

Lynne: So getting back to the Psychine advertisement in the 1907 issue of The Conservator, Mrs. Garside claimed to have been diagnosed as an incurable consumptive. Are consumption and TB the same thing? How was this ultimately cured? Has it been eradicated?

Colleen: Consumption was another name for TB. Its victims referred to as consumptives because as the disease progressed, the patient gradually lost weight as if the disease were consuming them.

TB has been around for a very long time, in fact, traces of it were found in human bodies 9,000 years old. Through the ages, different treatments have been advocated, some weirder than others. In the Middle Ages, treatment called for the “royal touch” - that is, kings and queens in England and France would touch those afflicted in the belief they would be cured of their symptoms. The 1800s saw physicians endorse the use of cod liver oil, vinegar massages and inhaling hemlock or turpentine. Treatments at the turn of the 20th century included some extreme measures such as the removal of infected lung tissue.

Today, TB can be effectively cured with a standard course of antibiotics, but in Mrs. Garside’s day there was no cure and treatment predominately included warmth, rest and good food.

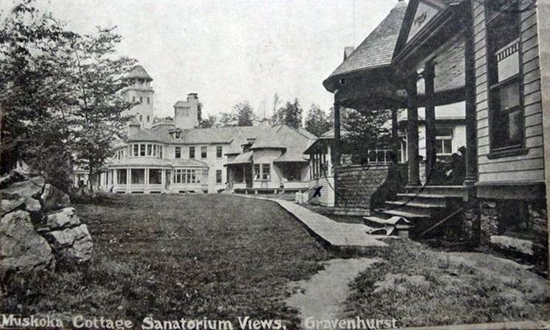

To accommodate the TB patients recovery, TB sanitariums sprung up across Canada, the first in 1897 in Muskoka. By 1918, there were thirty sanitariums across seven provinces. The purpose of the sanitariums was two-fold. It was thought that good food, proper sanitation, clean fresh air and rest would restore the patients to health, or at the least, improve it and it had the added benefit of removing the patient from close family and friends, thus preventing the spread. Originally, sojourns at a sanitorium were three to nine months, but as the fear of epidemics became more widespread during the 1920s, the duration increased to anywhere from two to five years.

Fortunately, the antibiotic streptomycin was developed and came into wide-spread use shortly after the Second World War, resulting in a rapid decrease in TB rates in the developed world. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) states that even today about one-quarter of the world’s population is infected with TB. Of this shockingly high number, only about 5-15% will actually become ill with TB. The rest will carry the infection - but not transmit the disease.

Today, TB tends to affect low- or middle-income countries at a disproportionate rate to wealthier countries. The WHO reports that about half of the world’s 10 million cases exist in just eight countries: Bangladesh, India, South Africa, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Philippines and China. Every year, 1.5 million people still die of TB.

Sadly, the Covid crisis has threatened to increase the incidence of TB in these countries. As healthcare systems pivot to fight Covid, they cannot keep up with health measures to treat TB. WHO director Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus fears that “the disruption of essential health services due to the pandemic could start to unravel years of progress against tuberculosis”.

Lynne: This is our special Valentine’s Day edition of the newsletter. We can’t end on such a depressing note. Do you have any happy news?

Colleen: Indeed, I do. Let’s go back to the subject of kissing. Now that we know the dangers of osculation, let’s remind ourselves of the medical benefits of kissing. According to Julie Enfield, author of Kiss and Tell - An Intimate History of Kissing, when a person kisses, chemicals are released into the brain, sending out a rush of positive sensations, lifting spirits no matter how dejected one might feel. The positive effects are not just reaped by the kisser but also by the receiver of the kiss. Think about a mother kissing a child’s “boo boo better”. Both the mother and the child seem to be comforted by this act.

Scientist have studied the chemical effects of a kiss on the brain. The lips are crammed with sensitive nerve endings which, when stimulated (even a light brush will do, apparently), send messages to the brain to release a crazy number of hormones. These hormones include oxycontin, dopamine, serotonin, and adrenaline – all hormones associated with feelings of euphoria, affection and bonding. A kiss can also send messages to reduce the level of cortisol (a stress hormone). And finally, kissing can dilate blood vessels which can help to reduce blood pressure.

While I’m not sure that early 20th century public health specialists were aware of the hormonal benefits of kissing, they had sense enough to recognize the social importance of it. Instead of banning kissing outright, they wisely preached good health hygiene measures - such as self-isolation when sick, covering the mouth when you sneeze or cough, proper nourishment, exercise, etc. etc. Which all sounds a little bit more than familiar right now, don’t you think?

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series