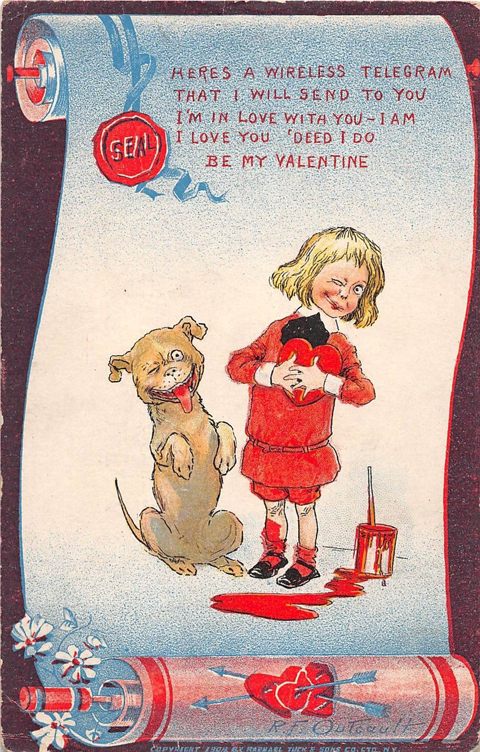

In Chapter 13 of The Innocent, Jessie, her friend, Frances and two of Jessie’s cousins, are sitting on her verandah, recounting stories involving their ten-year old friend Archie McKechnie. Frances recalls fondly the Valentine’s Day card Archie sent her earlier that year. “Orange you glad we are friends,” it said. Jessie is miffed at Frances’s suggestion that Frances held a unique place in Archie’s heart. Later, Jessie tells her brother’s friend, Millie, that she too received a Valentine’s Day card from Archie that year. The greeting provided to her, Jessie consoles herself, was even more special than that extended to Frances.

The story is part fact and part fiction. In real life, Jessie did receive a Valentine’s Day card from Archie in February, 1912. She kept it among her personal papers for her remaining 99 years. But the conversation on the verandah was of my imagination as was the delivery of the card to Jessie’s friend Frances.

But thinking about the fictional conversation recently, I began to wonder whether Archie might have sent a similar card to Frances, or to other female friends or to all of the students in his school classroom. Having considered the nature of the card, the history of Valentine’s Day cards and the manner in which Archie’s card was delivered, I feel confident that Jessie was the only, or was one of only one or two girls, to receive Archie’s romantic tidings that Valentine’s Day.

The card itself

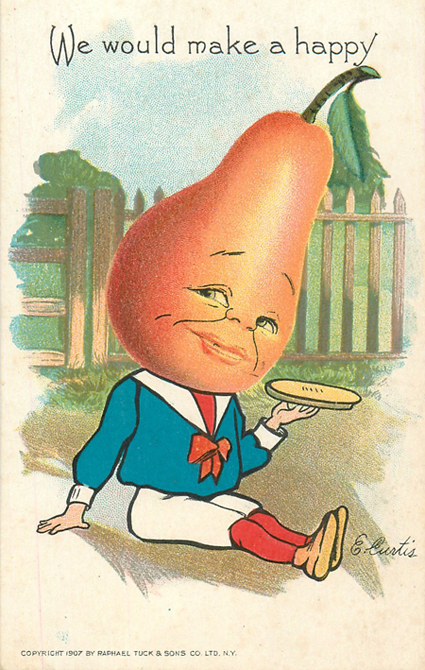

First, let me tell you more about the card itself. It was actually a postcard. In portrait layout, the words “We would make a happy ….” are featured above a short man, perched on the ground, one hand extended behind him supporting his torso and his oversized pear shaped head. There was no other expression of affection, either on the front or the back of the card. Indeed the card is not even signed by Archie. But in pencil across the portion on the back reserved for a brief note is Jessie’s cursive script: This was from Archie McKechnie.

The type of card

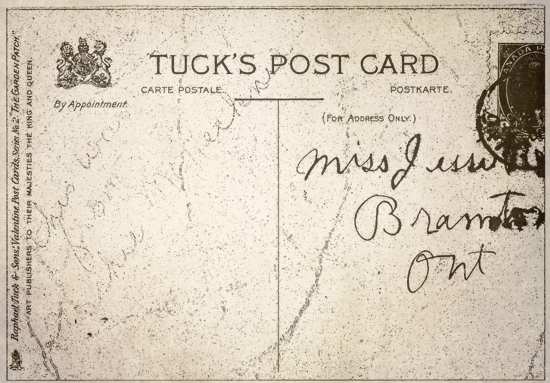

The printed text on the back of the card provided other instructive information. While most is in English, the card also contains some French (Carte Postale) and German (Postkarte). The royal coat of arms and the words “by appointment” make it clear that the publisher of the card had a royal warrant of appointment. The fact is reinforced by the wording along the side: Art publishers to their majesties the King and Queen.

But the text that allowed me to discover the most about the card was the largest: the card was stated to be a “Tuck’s Postcard,” produced by Raphael Tuck & Sons. The card itself was said to be part of the Valentine Postcards Series No 2. “The Garden Patch”.

With the wonders of the internet,1 I learned that Tuck and three of his sons were producers of greeting cards, calendars, paper dolls and toys, jig-saw puzzles and, significantly, picture postcards. Tuck, a graphic artist, and his wife Ernestine, founded the business in London, in 1866, following their immigration from Prussia. Their business, which began with the printing and distribution of reproductions of popular paintings, evolved into the reproduction of newly commissioned art for traditionally folded Christmas and other cards.

Raphael had a vision that a beautifully designed postcard could become a popular form of social communication but for the vision to be realized laws had to be changed. Before 1898, cards without an envelope or other covering could only be mailed through the British postal system if one side was entirely reserved for the address and stamp. The other side had to contain a message to the recipient and could therefore only contain a small picture. After four years of negotiation, the rules were changed. A larger sized card with a picture on one side and space for a message as well as an address and stamp on the other, could be sent through the British postal service. A new era for postcards began.

By the close of 1904 over 15,000 Tuck designed postcards were in production. Some said that the Tuck productions had a greater effect on the world of art than all of the art galleries in the world. Over the years, millions of the mass produced Tuck postcards were purchased by, or delivered to, people of every income level.

By the close of 1904 over 15,000 Tuck designed postcards were in production. Some said that the Tuck productions had a greater effect on the world of art than all of the art galleries in the world. Over the years, millions of the mass produced Tuck postcards were purchased by, or delivered to, people of every income level.

Though the Tuck enterprise expanded in the early 1900’s supported by offices in London, Paris, Berlin, Montreal and New York, it is likely that the card sent by Archie was printed in Britain, as were most Tuck cards sold in the North American markets. Other cards printed in Germany and distributed in Europe, are said to have been of better quality.

Finally, a note about how Tuck postcards were sold. Generally Tuck sold its postcards in paper envelopes containing “packets” of six cards (either six different images or six of the same image). Information about the set was provided on the front of the envelope. Information about other sets, was included on the back.

This is all very interesting (I hope you are saying), but from this how can we know that Archie likely only sent a Valentine’s Day card to Jessie or to Jessie and one other person in 1912? To answer that question, we need a bit more information about the history of Valentine’s Day card. I consulted two excellent sources: an article by Dr. Anna Maria Barry of the Royal College of Music Museum in London written for History Extra 2 and a beautiful history of Valentine’s Day cards assembled by google: The Heart of the Matter: A History of Valentine Cards From the Collections of The Strong National Museum of Play, Rochester, New York.3 I highly recommend them both.

History of Valentine’s Day Cards

According to Barry, the first evidence of the existence of Valentine’s Day cards dates back to the 1700s. The cards were handmade, decorated with flowers and love knots (not hearts) and often with a few lines of poetry. Pre-printed cards only emerged in the late 1700s. A few survive including this one from 1797:

Since on this ever Happy day,

All Nature’s full of Love and Play,

Yet harmless still if my design,

‘Tis but to be your Valentine.

Mass produced cards began to emerge in the next century. It is estimated that by the mid-1820s, 200,000 Valentine’s Day cards were delivered in London. The number was doubled in the 1840s and doubled again over the next 20 years. The growth in volume was attributable in part to the advancement in printing processes and in part to the reform of the British postal system (including the advent of the prepaid stamp and the setting of a flat one cent (or penny) delivery rate).

In the Victorian times, not all Valentine’s Day cards were sweet. “Vinegar” Valentine’s emerged intended to insult. One example, under the title ‘Miss Nosey’ contains the following:

On account of your talk of others’ affairs

At most dances you sit warming the chairs.

Because of the care with which you attend

To all others’ business you haven’t a friend.

Not surprisingly, relatively few examples of these cards survive.

In the mid-1800s Valentine’s Day cards became popular in North America as well as England. Hallmark Cards produced its first Valentine’s Day cards in 1913.

The Google Heart of the Matter history points out that around the same time, card manufacturers began to produce cards aimed at the children’s market featuring characters from comic strips and radio programs.

But the exchange of Valentine’s Day cards in schools – the creation of those decorative desk top collection boxes--only became widespread in the years following World War II. At that time, producers of Valentine’s Day cards began to sell packages of cards that included one card for the teacher and cards for the other students in the class.4 The cards were presumably priced to sell to this market.

How was Archie’s card delivered?

How was Archie’s card delivered? Was it put in the drawer of her school desk? Was it deposited under her door? No. Neither. From the back of the card we can see it was delivered by mail. Addressed simply to “Miss Jessie Roberts, Brampton, Ont”, it contained sufficient information for its receipt by the addressee in the small 4,000 person town.

A one cent stamp bearing the profile of King George V on the top right corner of the card is cancelled. Applying inflation, that one cent stamp would have cost $2.84 today5 (which makes me think we should all stop complaining about the $1.30 price of a first class stamp).

Conclusion

One other thing you should know is this: Archie McKechnie was the youngest of four children. His mother was a widow.

In all of the circumstances: the fact that low priced cards available for delivery to an entire classroom of students were not yet being produced; the price of stamps; the fact that the widow Mrs. McKechnie was likely careful with her funds; and the fact that Tuck sold their cards in packets of six, leads me to conclude that Mrs. McKechnie likely bought one packet of cards, and split them among her children. Archie would have been allotted one or at most two cards to send.

Maybe the story of my imagination whereby both Jessie and Frances received Valentine’s Day tidings from Archie in 1912, wasn’t as fictional as I thought it was.

_____________________

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raphael_Tuck_%26_Sons

2. https://www.historyextra.com/period/modern/when-was-valentines-day-first-celebrated-cards-history-saint-valentine/

3. https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/the-heart-of-the-matter-a-history-of-valentine-cards-the-strong/kgJS0t8TzcBFKw?hl=en

4. at

5. $1 in 1912 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $28.74 today, an increase of $27.74 over 110 year.

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series