Surplus Women

How many of you grew up with a “spinster” aunt or great aunt? I had three and I am not even including my now well-known great aunt Jessie. By the time I was born, Jessie had entered the matrimonial state, though she occupied it for only 15 of her 108 years. Thereafter, a widow, she was merely single.

My aunts Ina and Hannah, on my dad’s side of the family and Dot, on my mom’s, never married. I had always understood the reason for Jessie becoming a wife so late in her life (just before she turned 50) and my other aunts never becoming wives, related to the large number of men lost in the Great War. Over 60,000 Canadian men died in that war. There were just not enough men available for women of their generation to marry.

My understanding was reinforced on Remembrance Day, 1999 when my great aunt Jessie, then 96 years of age, appeared on Michael Enright’s First Person Singular on CBC Radio. In her short monologue available here she spoke about the toll that war took on a generation of women; how they traveled alone in life without husbands and babies; forging new paths in order to support themselves. The bravery and stamina of these women, chronicled by Jessie, was one of the inspirations for my Beneath the Alders series.

Only recently did it occur to me that I should look into the actual demographics of the time. I knew that in England these unmarried women were referred to as “surplus” or “superfluous”. Jessie referred to them in her CBC broadcast as “mis-spoused”. Google searches (always reliable of course) did not produce any references to such a concept in Canada. There were no hits for the phrase Jessie used either. Realizing that some in depth research would be required, I turned the question over to my researcher, Colleen Mahoney: Looking at the marriageable age group, were there exactly 60,000 less women in Canada than men in the years following World War I?

Surplus Women

While it was not clear that the notion of surplus women existed in Canada after the war, it certainly existed in Britain. Based on the 1921 British census, the death of over 700,000 British men in the Great War resulted in the number of unmarried women between the ages of 25 and 34 outnumbering unmarried men of the same age by almost a quarter of a million (1,158,000 unmarried women and 919,000 unmarried men).

However in Britain, the number of “surplus” women created by the war merely exacerbated an existing societal problem. It did not create the problem. The imbalance between men and women of marriageable age had existed in Britain for at least 70 years. The census of 1851 revealed that 30% of English women aged 20 to 40 were unmarried. By the end of that century, around a third of British women between the ages of 25 to 35 were unmarried. The trend continued in the Edwardian years. The reason: emigration. More young men than women emigrated each year from Britain.

Canadian census population

Colleen and I set out to run our own comparisons on Canadian men and women in the post-war years. We began by defining the “marriageable” quinquennial (five year) age groups. Using available Statistics Canada cohorts, we selected those between the ages of 20 to 24, 25 to 29 and 30 to 34. Possibly we would have been better served to include those men and women who were 18 and 19 but we could not include people of that age without also including those who were 15 to 17. We would then have been looking at people who were 12 to 17 at the end of the war. That did not seem right.

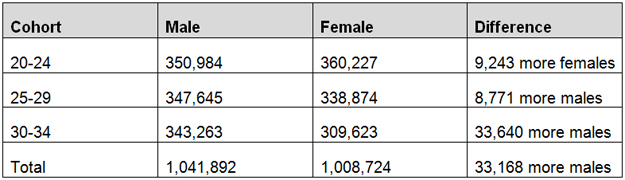

We then looked at data from the 1921 Canadian census. What we expected to see was an exact mismatch: within this 15 year age group, we thought we might see 60,000 less men than women—or given the disproportionate loss of unwell men of this age group from Spanish flu, perhaps the difference would be even greater. This was not what we saw. In total, of the more than two million men and women in Canada in 1921 between the ages of 20 and 34, there were actually more men than women!

Furthermore, looking at the three cohorts, there was only one where the number of women outnumbered men: the first cohort between 20 and 24 years of age. Since these men and women would have been between 17 and 21 years of age when the war ended, it did not seem likely that that the women in this cohort would have borne the entire mismatch brunt of the 60,000 dead. Indeed, the disparity between men and women of that cohort was not even 10,000.

Table 1: Census Canada results from 1921: 33,168 (1.6%) more males than females in total out of a total population of 2,050,616

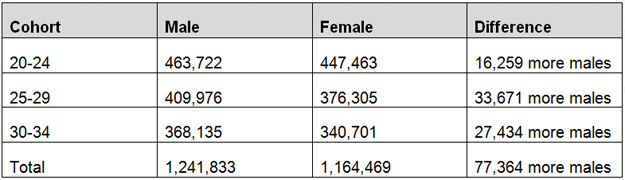

Stumped, we continued our investigations. We looked at the results of the next Canadian census—the one taken in 1931. Maybe it would be different. It was, but again not in the way we expected. There were more men and women in Canada in 1931 between 20 and 34 years of age (almost 400,000 more) but in fact the percentage of those who were men exceed the percentage of women by twice as much as was the case in 1921 (3.2% versus 1.6%).

Table 2: Census Canada results from 1931: 77,364 (3.2%) more males than females in total out of a total population of 2,406,302

No Surplus

We now had our explanation as to why the term “surplus” women had no resonance in Canada following the Great War. There was no surplus. How could that be we wondered given the number of men who died in the war—over 60,000 out of a population of eight million. Was there a disproportionately large number of women in Canada before the war? Did the war simply reduce the imbalance?

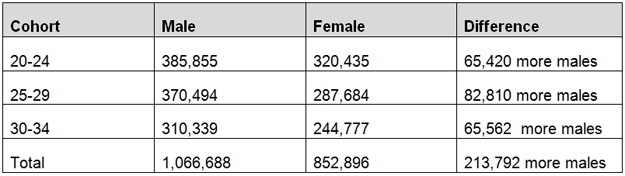

The answer is actually yes—sort of. In the last census conducted prior to the war, there were many more men than women in Canada in this age group. Of the just under two million men and women in the 20 to 34 year old age group in 1911, there were over 200,000 more men than women—an excess of men by 11%. Canada had at that time not a group of surplus women but rather a surplus of men.

Table 3: Census Canada results from 1911: 213,792 (11%) more males than females out of a total population of 1,919,584

Why a surplus of men?

Why were there more men than women in Canada in this age group in 1911, 1921 and 1931? Could the difference be explained by a difference in birth rates or infant mortality? No. The difference relates to immigration. In fact, the very circumstances that led to a surplus of women in Britain in this time period, led to a surplus of men in Canada. Statistics Canada reports that the first decades of the twentieth century (1914 -1918 excepted) were periods of great immigration into Canada. Often men immigrated to Canada on their own. This explains the greater number of men than women in each of these census years.

Why spinster aunts?

Why then were there so many spinster aunts after the war? There appeared to be more than enough men available for those aunts. We came up with a few theories:

Women can be particular

We wondered whether the number of unmarried aunts had something to do with the “high standards” of women. Perhaps women just needed a larger pool of men to choose from in selecting a husband. In the pre-war years, as shown from the 1911 census results, the difference in the number of “marriageable” men over women was 11%.

But if this was the explanation then wouldn’t it mean that we would have a disproportionately large number of unmarried/unpartnered women today? Based on the Canadian census results from 2016, the difference in the number of “marriageable” men over women is smaller than it has been in any of the periods considered in this article (not even one percent). So the answer did not lie in a need for a much greater number of men than women—or at least not solely.

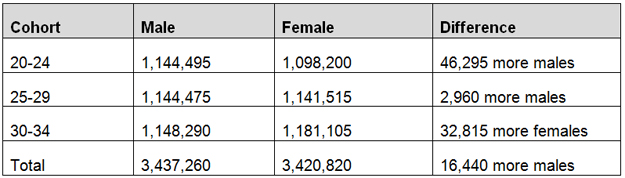

Table 4: Census Canada results from 2016: 16,440 (0.047) more males than females in total out of a total population of 35,151,725

Immigrants

A better explanation relates to the nature of the men in Canada. Those additional men captured in the 1911, 1921 and the 1931 censuses were immigrants to Canada. In writing about this situation, Statistics Canada suggests that these male immigrants tended not to marry until they had established themselves and at a time of relative prosperity. A large percentage of the men captured within those census numbers would not have been available for prospective brides as they had not yet established themselves. Once established, some at least, would have sent for brides from home.

War Injured

A better explanation for the number of unmarried aunts relates to the number of men injured in the war. Over 170,000 Canadian men were injured in that war, both physically and mentally. Unfortunate as it is, many veterans would not have been considered a good match. Some would never be fit for marriage.

Economy

Furthermore, men of the time would not have married if they could not support their wife and family. It was difficult for many injured war veterans to obtain and maintain employment, particularly in the immediate post-war years when Canada’s economy was in a state of decline. On top of this the postwar market was not sympathetic to men who returned home less capable and many employers were reluctant to hire veterans because they feared employees with physical or psychological wounds.

University Education

Lastly, in a bit of catch-22 situation, the additional education that Ina, Jessie and Hannah obtained-- in part to enable them to support themselves in the event that they did not marry--created limitations on the pool of those they could marry. When female university grads surveyed the field, their search may have been limited to men of a similar education. Men similarly educated would not have felt so constrained.

On their own

Although statistically there appeared to be more than enough men for women like Ina, Hannah and Jessie to marry, as a result of the war, there were not enough similarly situated, healthy, gainfully employed men.

A generation of young Canadian women were left to travel through life on their own. As Jessie said, “they took the only jobs available to women then: secretaries or low paying banking jobs. The few who could, went on to university and became teachers. Others to hospitals to become nurses. These were early workers in these fields who continued the building of strong foundations in our country.”

We owe them a debt.

To Order Your Copy of

The Beleaguered

select one of these links.