Perkins Bull Convalescent Hospital for Canadian Officers

Sometimes authors create mysteries that their readers must solve. Sometimes authors encounter mysteries that they must solve. The latter was the case with the incorporation into The Beleaguered of the story of the Perkins Bull Convalescent Hospital for Canadian Officers.

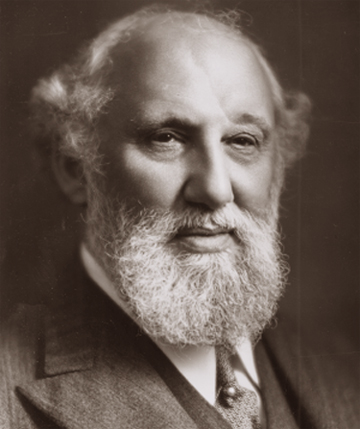

I first became aware of the existence of the hospital in the fall of 2018 while in the cozy offices of the Peel County Archives conducting research about the involvement of local men and women in World War I. One of the great resources available to Peel County history buffs are the volumes of local research conducted by Brampton’s own son-of-a-cattle-breeder-cum-lawyer-cum-businessman, Perkins Bull. After a career involved in all of the above and more, in 1934 at the age of sixty-four, Bull became an author ultimately publishing thirteen books mostly about human and natural history in Peel County. His research methods included gathering anecdotes and stories of local townspeople, a method of history writing considered somewhat unorthodox at the time.

The book of most interest to me in my writing of The Beleaguered was his third book, written in 1935, entitled From Brock to Currie: the Military Development and Exploits of Canadians in General and of the Men of Peel in Particular, 1791 to 1930. The titles of his books are all long and demonstrate advancement by starting at a distant point and ending at a more recent point.

I read and took notes about the manner in which recruitment occurred and troops were sent off in the early years of the Great War and about the role of clergy, the Red Cross, girls clubs and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Then I came across Bull’s description of the creation and operation of the Perkins Bull Hospital for Convalescing Canadian Officers—a hospital established in 1916 in London, England by Bull and his wife, Maria.

Here are some of the notes I transcribed from his writing commencing at page 461--a combination of his words and mine:

Perkins Bull himself was not allowed to enlist because he was overweight. The author was refused permission to enlist for active service, it being alleged against him that he had seen well over two score winters during which he had accumulated about 18 stone (256 pounds) and that he was further handicapped by a wife and seven small children, the oldest a daughter under 16. His brother [Jeffrey] was able to enlist.

Since it was practically impossible to get sleeping accommodations in London Mrs. Perkins Bull converted her home into a convalescent hospital for the reception and entertainment of Canadians who came overseas in connection with the war. In addition they secured a building across from them and turned it into a hospital. This was in 1915. The home was owned by Ernest Shackleton and was vacant as the explorer was in Antarctica. So in June 1916 the Perkins Bull Convalescent Hospital for Canadian Officers was opened.

Miss Dorothy Peel, now Mrs. Harry Simons, was commandant and in the big house 32 beds were installed and the staff mostly Canadian nurses-- there was a staff of 20.

Ran for three years and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Had on average 40 to 50 patients in it at a time [Not sure how that corresponds with 32 beds above unless this is in the 2 houses] throughout 1916, 17 and 18 until it closed in the summer of 1919.

How fascinating, I thought. I had already written a chapter for The Beleaguered where one of its main characters, a Canadian officer, convalesced in a London hospital. Perhaps I could move him from the Royal Free Hospital in which I had situated him to this Bull hospital—the hospital with a Brampton connection. As I read more about the hospital I was sure I wanted to do so.

The Bull hospital was the place to be for Canadians overseas. As the war progressed, some forty or more men would attend breakfast or dinner in the Bull home each day—sometimes twice as many as who were actually registered as patients within the hospital. Guests over the years included King George V and Queen Mary, Prime Minister Borden and other national leaders. In addition to enjoying fine food and discourse at the Bulls’ table, patients could play tennis on the Bulls’ private court and engage in after dinner dances.

The connection to Ernest Shackleton was the icing on the cake. How romantic, I thought, that while the world at large was gathering in trenches in Belgium and France, over their heads in mud, rats and lice, sacrificing the lives of thousands of soldiers for the acquisition of twenty feet of territory, there was Ernest Shackleton on a solitary mission exploring the pure white caps of the globe’s southern polar extreme. His contribution to the melee in which the rest of mankind was engulfed: the donation of his vacant home for the Canadian wounded. What a great story to feed into my book, I thought.

I transcribed all of the details about the hospital and how it came to be. As I shared my excitement about the story with archivist Samantha Thompson, she provided me with a booklet about the hospital that recently been published. All the Comforts of Home was a 5” x 8” glossy booklet about the Bull hospital. I took it home intending to read it later when I was ready to recast that one chapter.

A few months later, over my Christmas holidays, I considered how the new hospital location would fit into my narrative, the additional details that could be added about London life at the time, the activities that could be partaken in on the Bull and nearby Wimbledon grounds and the interesting Shackleton connection. After I had it sketched out, I turned to the booklet Samantha had given me. I found the contents of the booklet to be elucidating, affirming and then--confusing, at least in one respect.

The Bull hospital campus was, as can be gleaned from the above, comprised of two properties. The first property which became the location of meals and entertainment for the ambulatory patients of the hospital and other guests was the Bulls’ own home at 7 Heathview Gardens, Putney. The second property in which the patients slept was the one rented by the Bulls at 9 Heathview Gardens, Putney. Number 9 was the larger building of the two. In From Brock to Currie, Bull said that the second home--Number 9--was then owned by Shackleton; that it had been leased to Bull while the absent Shackleton was exploring Antarctica.

The booklet indicated that Number 9 had been let to the Bulls by a businessman from Leeds. The only reference to Shackleton in the booklet, was a reference to his position as a one-time occupant of the Bull home –the smaller Number 7. By that measure, Shackleton was not even a part of the play.

My immediate thought (it is just my nature) was that I must have erred in my transcription of those notes set out above. I obtained a copy of the actual pages of From Brock to Currie. For good or bad, they confirmed the accuracy of my notes.

I knew it was possible that it was Bull who had made the error–people often make errors in their recollections—but surely Bull would have known whether it was his own home or the home across the street that had the Shackleton connection. Even if in ordinary circumstances one could not recall the name of a party with whom one had entered a lease, one would surely remember doing so with a famous person. I thought Bull’s memory would be reliable on this matter.

I returned to the archives one evening and showed the discrepancy to Samantha and the other archivist, Kyle Neill. Samantha suspected the booklet had it right. Its author was Diane Allengame, the former archivist of Peel County. Samantha said that her research skills were meticulous. She would not have associated Shackleton with Number 7, unless that was where he had once lived.

Sensing that I needed to be convinced, and with no other patrons in the archives that night, we set about to resolve the mystery. While Samantha and I reviewed papers, Kyle took to the internet. As one of his enduring gifts to the residents of Peel, Bull donated to the Peel County Archives his personal papers relating to the creation of his books—his rough notes, newspaper clippings and other primary sources for the content he developed. Samantha retrieved from the bowels of the archives a box containing Bull’s papers pertaining to the relevant chapter of From Brock to Currie.

The first thing she directed me to was a handwritten manuscript for the chapter. Her thinking was that there may have been a transcription error in the creation of the actual book. Samantha explained that Bull had a number of people working on the books with him. Possibly his handwritten notes were not adhered to when the book was sent to print by one of these underlings. The manuscript however, confirmed my notes.

We dug further. Among Bull’s papers was a newspaper article from the opening of the hospital in 1916. The grand opening was attended by a number of dignitaries including Sir Charles Wakefield, the Lord Mayor of London and his wife, the Lady Mayoress. The newspaper quoted from the Mayor’s speech at the opening. The Mayor made reference to Shackleton, but not as the owner of the rented house at 9 Heathview Gardens, but rather as a former resident of the Bull house at 7 Heathview Gardens.

“That’s your answer,” Samantha said. She took the newspaper report as being more authoritative in the circumstances than Bull’s words. But I was still not convinced. Newspaper reporters can make errors, I explained. It was quite conceivable to me that the newspaper had inadvertently misquoted the Lord Mayor. “Now if we had a copy of the actual speech,” I said, “that would be another matter.”

Still I was not yet convinced. The speech could have been wrong. From my own experience I knew that political speech writers could make mistakes. The speech writer might not have been fully seized of the facts.

I clung to the view that Bull’s memory about the role of Shackleton in this housing arrangement –a passive uninvolved prior occupant of his own home or the man with whom he entered a lease-- would be reliable. And I liked the story. I really did. I resolved to write it as I had sketched it with Shackleton’s involvement but I would in the final chapter of the book, where I disclosed other deviations from reality (my book is fiction after all), disclose the confusion on the matter.

Ten days later I heard from Samantha again. Kyle had found some electoral registries on Ancestry. They showed quite clearly that at an earlier point in time, the occupant of the abode at 7 Heathview Gardens within Polling District No 2 Putney, was one Shackleton, Ernest Henry (Sir).

I confirmed that Shackleton had at least been in the Antarctica during WWI. Then I removed all references to him from my draft of The Beleaguered.

In June 2019, my friend Martha Whittaker and I went to Putney to see the two houses which are across the road from each other.

Samantha picked up the next document among the papers and handed it to me. It was a copy of the actual speech. The newspaper reporter had done an admirable job reporting on what had been said, assuming the Lord Mayor read from the prepared text. (Okay, I might be taking some literary licence here. I cannot be certain that the speech was in the documents box but I think it was. With COVID I am not able to enter the archives to confirm this.)

To Order Your Copy of

The Mending

select one of these links.