While I did all of the initial research for my Beneath the Alders series and for the first book in the series, The Innocent, I was greatly assisted in completing The Beleaguered and The Mending by the research skills of my good friend Colleen Mahoney, a pre-maturely retired librarian. In this article, Colleen answered specific questions I recently posed about the history of Canada’s postal service.

Lynne: Can you tell us about the postal system in the late 1800s and early 1900s?

Colleen: Quick note: for simplicity’s sake, I will be referring to Canada only as Canada rather than using its various other names before Confederation. Also, there are vast quantities of fascinating information available on this subject and I could go on for pages writing about it. But in this newsletter format I so will only touch on the most important and interesting things I discovered.

In 1850, the Canadian Parliament passed the Post Office Act, which meant that Canada was able to take control of its own postal system and, for the first time, collect the revenues generated through its services rather than remitting them to England. The Hon. James Morris was appointed Postmaster General and under his management an infrastructure created which allowed the government to set postal rates, build and maintain post offices, establish mail routes (by land and/or water), establish a system for sending registered mail, generate money orders and even set up a savings bank in select offices (more about that later).

Innovations in technology fostered many changes in how the mail was delivered and processed over the next few years. Railway service was added in 1854 (and removed in 1971), mechanical sorting began in 1896, rural mail delivery began in 1908. In 1954, letter carrier service was permanently reduced from twice per day to once and in 1969 Saturday deliveries were eliminated.

But despite all the changes over the years, until recently the post office was the hub of the community particularly in rural areas. In addition to offering essential service, it was a place of social activity, where neighbors came together, said hello and exchanged pleasantries and information and discussed topics important to their community.

Lynne: I think most of us are generally familiar with the services the post office provided but I’m not familiar with the Post Office Savings Bank. Can you tell us about it?

Colleen: In 1868, just after Confederation, the Post Office Savings Bank was created. At that time, post offices were more numerous than banks and served many more remote areas. The government believed that by setting up a banking service within the post offices, it would encourage more working-class people to save money. Apparently, Post Office Savings Banks were quite popular in Ontario. Only certain post offices were eligible to participate in the banking scheme, but those that could, would accept, hold and remit savings. Deposits had to be at least one dollar and not more than $1000 in one year with a ceiling of $3000 in total. Interest of 3% was offered in 1898.

The Post Office Saving Bank existed until 1968 but rapidly lost popularity long before that, as chartered banks starting wooing customers away with higher interest rates.

Lynne: How much did it cost to send mail in those days?

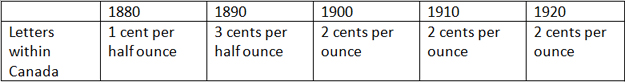

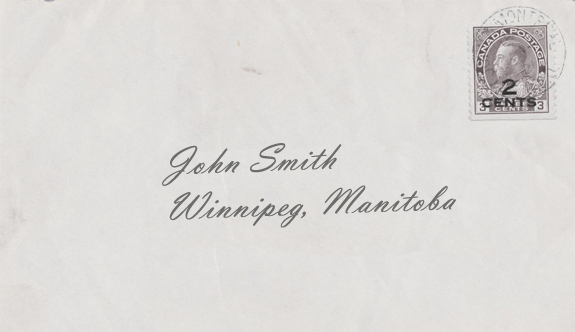

Colleen: As you can see from the chart below, the rates from 1880 to 1920 remained relatively stable over the entire period.

Parcel rates varied based on size and weight but, as an example, in 1898 a 1lb parcel to Germany would cost 34 cents while a ten lb parcel would be $1.30.

Lynne: How long did it take to move mail from one place to another back then?

Colleen: Very hard to say because of course it depended on many factors, the primary one being weather. Since 1764, when the first post office was established in Halifax, the mail has been delivered by foot, canoe, horse-drawn carriage, steamboat, trains, planes and automobiles of all kinds. The earlier modes of transport would have had to contend with all sorts of delays due to weather.

The use of steamboats greatly improved the efficiency for moving and delivering mail but only when the water wasn’t iced over. Steamboat routes were established along the St. Lawrence River and in the upper Great Lakes which could then connect Parry Sound, Collingwood, Sault Ste. Marie and Fort William with the US postal service. Mail was delivered to England once per week via Quebec in the summer and Halifax in the winter (with a stop-over in Newfoundland).

The rail industry exploded in the 1850s so of course, it was only logical to use trains to move mail. Trains not being as weather dependent as boats greatly improved the movement of mail. The Post Office started putting mail clerks on trains and boats so that the sorting could be done along the route. By the early 1860s, especially equipped cars called railway post office (RPO) cars were added to trains. RPO clerks were an elite group that could sort mail by the towns along the route as well as for connecting trains at stations that would go off in another direction. It has been said that the clerks could sort one letter every two seconds on these trains. In addition, there was a letter slot on the side of these trains and mail could be picked up at various places without even stopping by means of a catch arm which would swing out and snag the mail bag. Simultaneously, the RPO clerk would kick the mail bag or bags with sorted mail off the train and onto a platform for the local mail clerk.

In its heyday, the RPO employed 1385 men and women, and covered about 40,000 miles using 834 cars. The popularity of rail cars began to wane in 1950 when airplanes became a more reliable and faster mode of transport. And even trucks offered more flexibility than trains. The last RPO was discontinued in 1971.

Lynne: What could be sent by mail and what was prohibited?

Colleen: It’s an interesting list of what was and was not allowed. The Canadian Official Postal Guide of 1880 lists:

Materials permissible to send: Books, bulbs and roots, circulars, cuttings and grafts, deeds, eyeglasses, hand bills, letters, lithographs, maps, music, newspapers, pamphlets, parcels periodicals, photographs, insurance policies, post cards, school returns, seeds, sheet music.

Materials not permissible to send: Gold or silver (unless it was going to the US), jewels or precious articles that may be subject to Custom duties (can only be sent by registered mail if going outside the Dominion of Canada), explosives, dangerous or destructive substances or liquid, or any matter that is likely to cause injury to persons or things; glass matter except eyeglasses or microscopic slides; liquids, matches, leeches or fruit; obscene, immoral, seditious, disloyal, scurrilous or libelous materials.

I’m not yet sure why silver or gold was allowed to be sent to the US but not anywhere else.

Lynne: I understand that Benjamin Franklin became a wealthy man while he served as Postmaster General of America. How did this come about?

Colleen: Well, I think if would be fair to say that Franklin’s wealth did not come from his earnings as Postmaster General, although the position certainly allowed him to become successful by other means. In the 18th century, newspaper printers often acted as postmasters. The comings and goings of people from various places in the course of delivering mail, allowed postmasters to gather information from far and near, print it in their newspapers and redistribute it. Furthermore, the postmaster could decide which newspapers could be distributed free through the mail and which could not. In 1737, Franklin, a resident of Philadelphia, was the owner/publisher of The Pennsylvania Gazette a newspaper which though successful was not being delivered for free. When the position of the city postmaster came open, he leapt at the opportunity. In his autobiography, of his new position, Franklin says, “found it of great advantage; for, tho’ the salary was small, it facilitated the correspondence that improv’d my newspaper, increas’d the number demanded, as well as the advertisements to be inserted, so that it came to afford me a considerable income”.

Clearly Franklin had some aptitude for the role because in 1753, with a little lobbying, he became joint Postmaster General for the Crown along with a fellow named William Hunter. Franklin is credited with introducing a simple accounting system for postmasters and establishing a penny post system in which letters were delivered within urban centres for a penny. Under his watch, all newspapers were delivered for a small fee and newspapers published the names of people who had letters awaiting them at the post office. To improve the speed of mail delivery, Franklin, ordered that mail couriers travel by night as well as day and had odometers placed on the axles of delivery vehicles to determine the most efficient routes.

When the French ceded the Colony of New France to the British in 1763, Benjamin Franklin’s authority as Postmaster General was extended to this new territory. So funnily enough, Franklin was Canada’s first Postmaster General. He held this position until 1774 when he became embroiled in the Hutchinson Affair and was seen as too sympathetic to agitators in the colonies.

Lynne: Interesting. What about the postmasters in Canada? Were they well paid?

Colleen: For the most part it depended on how much business the post office did. Though Franklin was describing Canada in the mid to late 1700, much of Canada was still sparsely populated 100 years later. In 1870, a payment system was adopted in which country postmasters were compensated by a fixed annual salary based on what commission the postage revenues of each office would produce. Postmasters that were responsible for a busy office (presumably in a town or small city) would be compensated more generously than one that did little business in a remote area post office.

For instance, there was a minimum salary of $10 dollars at all post offices no matter what. But if your revenue exceeded $800 you would receive 40% of the revenue and a further 25% of revenues over $800. Where post offices generated more than $2000, an allowance was provided to help with cost associated with rent, fuel and electricity.

Lynne: An allowance was allocated for offices with revenues exceeding $2000. What was the deal with those that did not exceed $2000?

Colleen: In 1870, as is the case today too, post offices were often located inside other businesses. The postal revenue would have been supplemental to the primary earnings the business generated, and therefore, the government did not see the need to pay for something that was already paid for by the owner.

Additionally, in small rural areas it was not unheard of for post offices, to be located in homes and provide a family a little extra income. In fact, my aunt and uncle, Hubert and Jean Demaer, were postmaster and postmistress in the small town of Success, Saskatchewan from 1969 – 1977. The post office was located at the front of the house with all the accompanying accoutrements – cubbyholes, stamps, ink, scales, etc. My aunt and uncle would have to be available during certain hours of the day, but they had a bell which customers could ring to get their attention and they could pretty much carry on with their day otherwise.

Lynne: What else did you discover that you found interesting?

Colleen: So glad you always ask that question – there were so many things but I’ll only mention two.

1. The Postmaster General set up a “Dead Letter Office” in Ottawa to which any undeliverable mail would be forwarded. I thought this sounded a little like something out of a Harry Potter novel. After making every effort to determine where the mail could be forwarded or returned to, anything left behind was destroyed. Sadly, the name was changed to the far less “haunting” name of Undeliverable Mail Office in 1954.

2. The early postal guides stated that when sending letters to hot climates, they should never be sealed with wax. “Such a practice is attended with much inconvenience, and frequently with serious injury, in consequence of the melting of the wax and the adhesion of the letters to each other. In all such cases, use either wafers or gum, and advise your correspondents in the countries referred to, to do the same.”

To Order Your Copy of

The Mending

select one of these links.