While I did all of the initial research for my Beneath the Alders series and for the first book in the series, The Innocent, I was greatly assisted in completing The Beleaguered and The Mending by the research skills of my good friend Colleen Mahoney, a pre-maturely retired librarian. In this article, Colleen answered specific questions I posed about nursing in and around World War I

Lynne: Is it true that Canadian nurses in World War I were considered to be officers?

Colleen: Yes. In World War I, Canada created a nursing corps called the Canadian Army Nursing Service. For the first time ever, nurses served as fully integrated members of the Canadian army. The nurses were referred to as “sister soldiers”. They were in a unique position as they were fully enlisted, commissioned officers (lieutenants except for the matrons in charge of hospital units who were captains). In fact they were called “Millionaire Colonials” by some because of the pay they received: basic pay of $2.00 per day, a “messing” allowance of $1.00 per day, a field allowance while overseas of $0.60 per day and travel allowances. They were also entitled to travel first class, did not have to participate in meal preparations and were provided with “home sisters” to assist with housekeeping and shopping.

The Canadian nurses were the envy of their British and American counterparts who had no rank and were paid much less. Because of their blue dresses and white veils they were nicknamed the "bluebirds."

Lynne: How did a person qualify to join the corps?

Colleen: Not just anyone could be a member of the Canadian nursing corps. In order to qualify for the corps a woman had to be:

- a British subject

- a graduate of a three year nursing training program

- single or widowed

- of good moral character

- physically fit

- between 21 and 38 years of age on enlistment

Now even though I said that those were the requirements, there were exceptions. Apparently ten to fifteen percent of the corps was married at the time of enlistment or secretly married after enlisting. But nurses had to resign if they became pregnant. Also apparently many nurses adjusted their ages in their attestation papers. In reality, their ages ranged from 19 to 56 with the average being just under 30.

The members of the corps volunteered for service. They were not conscripted. There was never a shortage of candidates. In January 1915, for instance, there were 2,000 applicants for 75 positions. Over three thousand Canadian women served in the nursing corps.

Lynne: What kind of work did the nurses do in the corps?

Colleen: Their work was gruelling. It was also dangerous. The nurses worked in all types of army hospitals including the casualty clearing centres near the battlefronts. By the end of the WWI, approximately 45 nursing sisters had died in service, succumbing to enemy attacks, including the bombing of a hospital and the sinking of a hospital ship, or from disease.

On several occasions, nurses were in the territory where poison gas was still active and had to wear gas masks. On the Western front, poison gas infused soldiers’ clothing so that when nurses bent over the men either to care for them or remove the contaminated clothing, they too breathed the gas and suffered the effects of it. Many nurses spoke of long-term permanent lung problems after the war.

Lack of food and sanitary water and malaria were particularly problematic in the Eastern Mediterranean. Many nurses wound up sick with water borne diseases which resulted in their deaths or necessitated their evacuation from the area.

The nursing sisters are not to be confused with the nurses’ aids. Thousands of women made their contribution to the war effort by serving as nurses’ aids, including Amelia Earhart who served as a nurses’ aid in the Spadina Military Convalescent Hospital in Toronto during World War I. Nurses’ aids were not required to meet the entrance qualifications of nurses and were not members of the corps.

Lynne: What were those three year nursing programs referred to in the entrance requirements for the corps?

Colleen: Today, in Ontario, students attend universities in order to qualify as registered nurses or college programs to qualify as registered practical nurses. In either case, the curriculum includes time spent working in hospital settings where practical knowledge is acquired.

But prior to WWI and for decades afterwards nursing programs in Canada were operated solely by hospitals. Because the presence of nursing students allowed hospital wards to be fully and yet inexpensively staffed, hospital nursing programs proliferated. From early programs in St. Catharines (1874), Winnipeg (1887) and Halifax (1890), hospital based nursing schools eventually numbered seventy by 1909 and over two hundred by the 1920’s.

Students learned the “practical nature in the art of nursing” as well as academic subjects like chemistry, sanitary science, popular physiology and anatomy and hygiene. Under the apprenticeship model, students undertook a three year program, attaining their nurse’s cap after successfully completing their three month probationary period. In the third year as a senior, many nurses assumed supervisory roles.

The hospital training was demanding. Students often worked six days per week rotating between day and night shifts. In addition to tending to the patients on the wards, the students assisted in the delivery of babies and in surgeries.

Lynne: Where did nursing students live?

Colleen: Given their hours and the demanding nature of their program, it was determined that nursing students should live within a student residence. The first nursing student residence in Canada was at Toronto General Hospital.

Nearby Women’s College Hospital raised money to purchase a house for its student nurses. It opened in June 1918 with 18 bedrooms and five bathrooms. Each bedroom held two to four beds. Those students would have known their classmates extremely well at the end of their program!

Lynne: What was it like to live in those nursing residences?

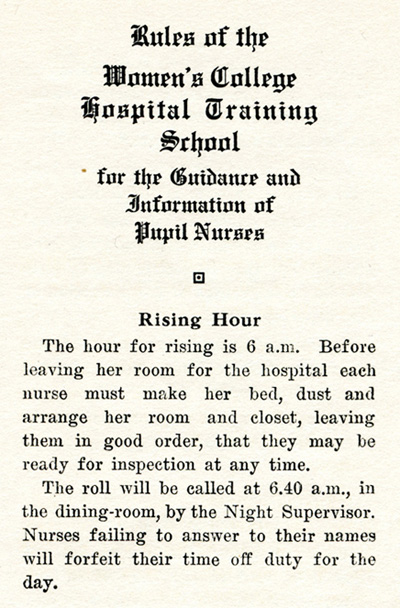

Colleen: Well, there were a lot of rules! Students had to comply with strict rules both within the hospital and within the nursing residence. At Women’s College Hospital, rule books were issued to the students covering everything from curfews, visitors, hours of sleep, bathtub use, how to make a bed and how to store clothing.

From Nursing Residences Memories of Women’s College School Nursing, See citation below

It is reported that in 1959 a senior nursing student in Vancouver was suspended from the nursing program for kissing a man. She was not even within the hospital’s premises at the time she displayed that affection. But that was consistent with the rules applicable to nurses: the entrance requirements for women in the Canadian Army Nursing Corps in 1914 applied to nurses in Canadian hospitals for decades to follow. Those who married were not able to stay on.

For that and other reasons, prior to WWII, most nurses left the hospital after their graduation. However that changed in the 1940’s when the war and technology increased the need for nurses within hospitals.

Some Sources:

History of Nursing Education in Canada by the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing https://www.casn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/History.pdf

Nursing Residences Memories of Women’s College School Nursing, http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/community-stories_histoires-de-chez-nous/womens-college-nursing_ecole-infirmieres-womens-college/story/mrs-chase-a-model-patient/

Reconsidering Nursing’s History During Canada’s 150 By Lydia Wytenbroek, MA, BA, BSN, RN , Helen Vandenberg, PhD, RN https://www.canadian-nurse.com/en/articles/issues/2017/july-august-2017/reconsidering-nursings-history-during-canada-150 Jul 03, 2017

Sister Soldiers of the Great War: The Nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, By Cynthia Toman, UBC Press, 2016

Toronto General History, https://www.uhn.ca/corporate/AboutUHN/OurHistory/Pages/toronto_general_history.aspx

To Order Your Copy of

The Mending

select one of these links.