While I did all of the initial research for my Beneath the Alders series and for the first book in the series, The Innocent, I was greatly assisted in completing The Beleaguered and The Mending by the research skills of my good friend Colleen Mahoney, a pre-maturely retired librarian. For this newsletter, I asked Colleen questions about chaplains and padres in the military.

Lynne: Firstly, I sometimes hear clergy in the military referred to as chaplains and at other times padres. Why is this? Which is correct?

Colleen: “Chaplain” is the official title for spiritual leaders in the armed forces. The term “padre” was initially only used when addressing Catholic chaplains, but in today’s parlance it is used when speaking to all chaplains – regardless of their religious affiliation. This usage dates back to the early 19th century, when British soldiers in India began to use the term to refer to any chaplain - Catholic or Protestant. It served as a catchall phrase for a soldier who didn’t know which of the many monikers might be attached to a chaplain of a specific denomination, i.e., pastor, minister, father, reverend, rabbi, monsignor, etc. In this article, I will use the terms interchangeably.

Lynne: What is a chaplain then…and what are their duties?

Colleen: The Canadian Department of National Defence states that, “Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) chaplains are responsible for fostering the spiritual, religious, and pastoral care of CAF members and their families, regardless of their religious affiliation, practice, and/or belief.” Their specific duties include providing an active, personal, and supportive presence, officiating at special functions, services, events and ceremonies, advising the chain of command on various ethical, moral or spiritual issues, referring CAF members and their families to other helping professionals and providing compassionate support during significant life events.

Lynne: The DND mandate sounds rather vague. Can you give us some examples of some of the work that engage chaplains on a day-to-day basis?

Colleen: Sure! Historically, chaplains were central to efforts by army leadership to maintain discipline and encourage desired behaviours. In the late nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century, when membership in the local militia was popular and attracted many young men, according to Duff Crerar, the author of Padres in no man’s land: Canadian Chaplains and the Great War, (which I highly recommend as a well-researched, fantastic reference and an easy read), “the antics of rowdy militiamen…filled summer columns of the Canadian press for years, suggesting that the army was an ideal instrument for the moral corruption of husbands, sons and brothers. Traditionally, evenings were spent at the canteen, the recreational heart of each camp, where vendors did a roaring trade. Militia Headquarters routinely banned strong drink and just as routinely these orders were disobeyed or ignored. Many Protestants welcomed the YMCA into the camps to run dry canteens and recreational programs. By the turn of the century these ministries, which included Bible studies and evangelistic services in the evenings, were a routine feature of camp life. The padres were expected to substitute wholesome entertainment and sports for liquor, beer, cards, and dice.”

Further, chaplains were “mature enough to guide and influence men of widely varying backgrounds and ages…. The chaplains were a diverse group: Conservatives, Liberals, imperialists, reformers, idealists, and pragmatists all came to the colours, along with clergymen in favour of “Church union” and those opposed to it. Some scorned Prohibition, while others were crusaders for purity and probity. Yet most shared some common characteristics and concerns. Effective chaplains were leaders of men, respected for their manly nature and prowess in sports. A number were noted athletes and outdoorsmen.”

But let’s look at a more contemporary case. Padre Christy Lacey, a British chaplain currently serving in the Middle East, describes her life as much more than leading services and preaching, bible studies and prayer groups – what she calls the “God stuff”. She says it’s the small stuff, like baking and distributing cookies that make people feel loved and valued. She emphasises that the men and women of the armed forces are far away from their friends, families and normal support groups. So above all, she says, the greatest gift she can give is to support, advise and, above all, listen.

One last note on this. Not to be confused with warrior priests, chaplains were, and still are, “non-combatants” though there have been some exceptions to this rule over the years.

Lynne: What is the history of the “padres” in the Canadian Armed Forces? What were their beginnings?

The Canadian Chaplain Service first came into being on June 1, 1921. It has cycled through a few other names since, most recently in 2014 when it became the Royal Canadian Chaplain Service. That Service has approximately 200 Regular Force chaplains and 145 Reserve Force Chaplains.

However, long before 1921, it had become common practice for clergymen to attach themselves to local militias and take part in the regiment’s parades, ceremonies, etc. acting as their chaplain. Early Canadian/British battles, such as the War of 1812, the Fenian Uprising, the Red River Rebellion and the Northwest Rebellion, all had volunteer chaplains accompany them to battle. As you would expect, they led prayers, gave last rites, conducted burial ceremonies, provided some first aid and doled out considerable quantities of encouragement and compassion.

Lynne: How were the chaplains selected for service?

Colleen: With much difficulty! The Red River Rebellion of 1869 illustrated this problem beautifully. The commander of the expeditionary force headed for Manitoba was opposed to including chaplains but was told by the Minister of the Militia, George Cartier, that he would be accompanied by an Anglican parson and an Oblate priest. When the Wesleyan Methodists found out about this, they accused Cartier of discrimination. Even Egerton Ryerson leapt into the fray. “He thundered against the dangers that Anglo-Catholic chaplains held for young Methodist volunteers and the influence popish priestcraft had on Cartier’s choice of chaplains, warning that voluntarist principles were in danger so long as governments, not denominations, controlled chaplaincy appointments.”

The battle played out in the House of Commons and the newspapers. The Leader of the Opposition, Alexander Mackenzie, a Baptist, stated that, “chaplaincy selection was an important indicator of the government’s view of the relations between church and state”. In the end, Sir John A. Macdonald’s government, knowing that Catholics would refuse to go to battle without a priest, had no choice but to allow the major denominations to select additional chaplains more to their liking.

This conflict had a sequel in 1885, when an expedition was planned to deal with the Northwest Rebellion. This time it was resolved by allowing each unit to select its own chaplain. This solution was acceptable to all and there was a mad rush to find padres and hustle them west. All denominations were represented save the Methodists. Apparently, they couldn’t find a unit willing to take them.

A good solution had been hit upon and everyone was relatively happy, so you would think that this would be the end of the denominational bickering. But no! It played out again at the onset of the Boer War (which included more fireworks in the House of Commons – when Wilfred Laurier was accused of favouring the Catholic Church over the Anglican one) and again at the start of World War I. Perhaps this is why the Government finally decided to establish the Canadian Chaplain Service in 1921, despite the expense it would incur.

Lynne: So how did chaplains fare in the battlefield in war time?

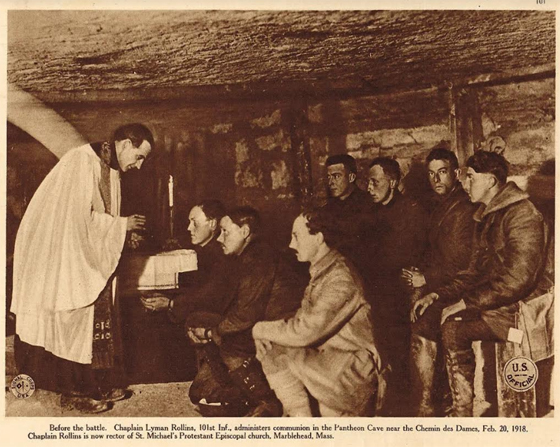

Colleen: If the mission of the padre was simply to administer church rites and preach, then mission accomplished for the most part. But in addition to the “God stuff”, padres who were considered to be the most successful were those that showed bravery and commitment to the men on the battlefields in times of action. The more visible a padre was during a battle, the more popular he was with his men. T.B. Hardy, a British chaplain of World War I said this best, “The line is the key to the whole thing. Work in the front line and they will listen to you. If you stay back, you are wasting your time. Men will forgive anything but lack of courage and devotion.”

Furthermore, one of the unexpected aspects of war is the boredom and tension that soldiers experience during lulls in battle, which can lead to low morale and any number of bad outcomes. It was at times like these when padres really had an opportunity to shine.

Successful padres exhibited good humour, the ability to relate to the common soldier and a talent for organizing recreational activities during downtimes, which kept the units cohesive, upbeat, focussed on their mission and ready for action…whenever it might happen.

Not only were such padres popular with the men, they were popular with Canadians back home. Stories of the padres’ courage on the battlefield were broadly reported in newspapers and from the pulpits of their churches. Churches associated with one of the “holy heroes” benefited from the ensuing popularity by swelling congregations and the admiration of other denominations. As one can imagine, a chaplaincy post became a much sought-after appointment.

Lynne: Can you tell us about some of the padres that stand out as “holy heroes” to you?

Colleen: With pleasure! I’ll tell you about three. The first of these is the Presbyterian padre “Fighting Dan Gordon”, who took part in the Northwest Rebellion. Gordon was said to be cool under fire, visiting men on the front line when in a pitched battle and running with ambulance wagons so he would be ready to assist when needed.

Another is Father Peter O’Leary a Catholic priest in the Boer War, who at the “advanced” age of 49 years, joined his much younger regiment in Africa. He took part in in strenuous marches, delivered first aid and last rites under sniper fire on the battlefield and offered encouragement under the direst of circumstances.

Perhaps most memorably, the World War I gave us Canon Frederick George Scott who was 54 years old in 1914 and served straight through to the war’s end in 1918. When Canadians began shipping out from England to France, Scott found he had been assigned to a hospital unit in England. He was determined not to be separated from his men, so he smuggled himself on board a transport boat and made his way to Flanders. He of course was caught, but managed to talk his way into the Fourteenth Battalion as an extra chaplain. While ministering on the front line was forbidden to padres, especially during intense battle, Scott flouted the rules and made his way into the trenches on a regular basis. His good humor and comradery made him a very popular companion on the front. He was caught up in the Second Battle Ypres where chlorine gas was deployed. In the confusion of wounded, dead and dying soldiers as well as civilians, he helped load ambulances, found and distributed rations, buried the dead and comforted all those in need. His courage and kindness became legend.

Crerar tells us that Canon Scott won the admiration of the medical staff by his tireless work with the wounded and dying in hospitals, which included, “reassuring the anxious, praising the wounded, taking last messages from the dying and dispensing cigarettes and communion as appropriate”. At one point, he got his hands on a motorcycle and could been seen zipping along Belgian roads with a side-car full of bibles and a portable altar strapped to the back of it.

Well known amongst the troops, his tag line following a battle was, “It was a great day for Canada, boys”, meaning you did yourselves and your country proud and don’t forget it.

Note: All quotes are from of Padres in no man’s land: Canadian Chaplains and the Great War (2nd Edition) by Duff Crerar, published by McGill-Queens Univeristy Press, 2014.

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series