While I did all of the initial research for my Beneath the Alders series and for the first book in the series, The Innocent, I was greatly assisted in completing The Beleaguered and The Mending by the research skills of my good friend Colleen Mahoney, a pre-maturely retired librarian. For this newsletter, I asked Colleen questions about the road to the creation of TB Sanitariums in Canada.

“Notwithstanding that the disease is so destructive, consumptive patients are often refused admittance in to the general hospitals on account of beds being occupied by more urgent cases and because of the lingering nature of the disease and its almost certain fatality in its advanced stage. These very peculiarities should give the patient the strongest claim upon our sympathies… the long wasting disease will ruin him and bring destitution to those dependent upon him.”

William James Gage, December 6, 1894

Lynne: Why did it take so long for the idea of a TB sanitarium to be taken seriously?

Colleen: From 1850 to 1899, the leading cause of death in Toronto was Tuberculosis (TB), or consumption as it was also known. Children under the age of one year made up approximately 40% of those deaths. Until 1882, it was generally believed that TB was a hereditary disease that was brought on, or worsened by, poor diet, cramped housing and substandard hygiene. But in that year, Dr. Robert Koch was able to prove what he had long suspected - TB was not a hereditary affliction, but was actually the result of an airborne bacteria which was passed directly from person to person or through dust particles infected with the patient’s sputum.

Unfortunately, the medical community and governments were slow to absorb and process this new information and, in fact, it wasn’t until the mid-1890s that TB was finally listed as a contagious disease in Ontario! Once past that hurdle though, all involved sought new methods to slow the spread of the contagion and, find ways of treating those already in its grip.

Lynne: When was the idea of a sanitarium to treat those with TB taken seriously?

Colleen: The idea of the sanitarium as a place to treat TB was not particularly new. Many in the medical community had long thought TB was a disease of industrialized cities, where its citizens were densely housed in less than sanitary conditions. They postulated that if you withdrew the TB patients from these conditions, while providing them with fresh air, sunshine, rest and plenty of nutritious food, it would go a long way in improving their health. To that end, a pioneering doctor in Germany opened the first sanitarium in 1854. And very often, a sojourn in the sanitarium did improve the health of the patients…. at least initially. Sadly though, many patients would go on to relapse after returning to their previous lives.

So, in 1882, knowing that TB was contagious and not hereditary, forward-thinking doctors decided to give the sanitarium another look. Not only could it provide the conditions that would improve or cure the disease, it would isolate them, so that they could not pass it on to others. It seemed a sensible way to deal with the many cases in Toronto. But the movement needed an influential leader.

Lynne: Enter William James Gage?

Colleen: Yes, a you mentioned in this newsletter [Brampton Connections article] , the loss of 19 of students to this dread disease caused Gage, to leave the profession of teaching. He developed a a lifetime passion for fighting TB.

Years later, and well-established as a successful businessman in Toronto, Gage decided he had the means and clout to take the fight against TB a huge step further. He educated himself about the disease and discussed the latest thinking in prevention techniques with medical specialists. He enlisted the help of other Toronto business leaders, including Hart Massey, Hugh Blain and Drs. D.E. Thompson and N. A. Powell, who together founded the National Sanitarium Association (NSA), with the aim of opening a sanitarium solely dedicated to treating consumptive patients.

Lynne: What were their first challenges?

Colleen: The first order of business was raising funds. To kick things off in a spectacular fashion, in May of 1894, Gage pledged $25,000 of his own money (of what he estimated would be a total cost of $50,000), to build the first specially designated sanitarium for consumptives in Canada. He proposed a site in High Park.

More than a year of dickering ensued, where alternate sites were proposed and rejected. Letters to the editor were written in support of the proposal, while some politicians seemed to suggest Gage had ulterior motives and he should back away. It has been written that a public outcry from the residents in the proposed areas were responsible for the delay and this could well be true. It is easy to imagine that few would be in favour of a sanitarium in their neighborhood (just as we deal with “NIMBYism” today for things like out-of-the-cold programs). But the fear is also easy to understand. Men, women and children were dying in droves of the “dread consumption” and the accepted knowledge was that it was spread from person to person, or in dust particles contaminated with the expectorate of patients when coughing. And, there was no sure-fire cure. Who, honestly, would want to risk living beside a hospital filled with consumptives?

Well, it turned out the answer was no one. But, Gage was not going to let this stop him. As an alternative, he began courting the mayors and councils in other locations or in some cases, it appears as though they may have been wooing him. By the summer of 1895, city officials from Hamilton, Huntsville and Gravenhurst, to name just a few, had approached the NSA to promote their areas as a possible site.

While the dickering continued, Gage decided to put his time to good use. In December of 1894, he, together with some well-known city doctors, went on a fact-finding tour to sanitariums in Europe. On returning, he said, “I have visited some hospitals in Great Britain and Germany that have been in operation for a number of years, devoted entirely to the treatment of consumption and diseases of the chest, and have secured various plans and much information that must prove of value if we can persuade the people to go on with the proposed hospital in this city.”

Alas, the hospital in High Park was not to be so Gage began to ponder Muskoka as a possible location. It was similar to the environment and climate of the world-renowned sanitarium on Lake Saranac in upper New York state.

Gage made a trek to Muskoka and upon his return, he announced that he would be recommending the Robinson farm, located close to Gravenhurst, as his preferred site. To seal the deal, Gravenhurst pledged $10,000 toward building suitable accommodations for patients. This gift in addition to the $25,000 Gage had already pledged, was enough to get the ball rolling.

Lynne: What was the next hurdle?

Colleen: The second hurdle to overcome was funding for the operation of the hospital. Consumptive patients required longer stays and more food than hospitals were accustomed to providing. It was estimated that the amount required to properly care for a patient in the hospital was $7 to $9 per week. Gage expected that various levels of governments would provide about half the amount required. As to the remainder, he said, “There will, I trust be a number who in memory of some loved one, and who, sympathizing with those unfortunately afflicted, may desire to endow a ward or a bed, and thus provide a permanent [source of] revenue. In addition, there will always be a few who will be able to pay for their own maintenance, and this class should furnish a source of revenue.”

Gage was not wrong. In addition to the $25,000 he put toward the hospital, Mr. Hart Massey also pledged $25,000, Mr. William Davies $10,000 and Mr. W. Christie $5,000. Additional funding was sought through campaigns such as Christmas Seals and the White Rose Day.

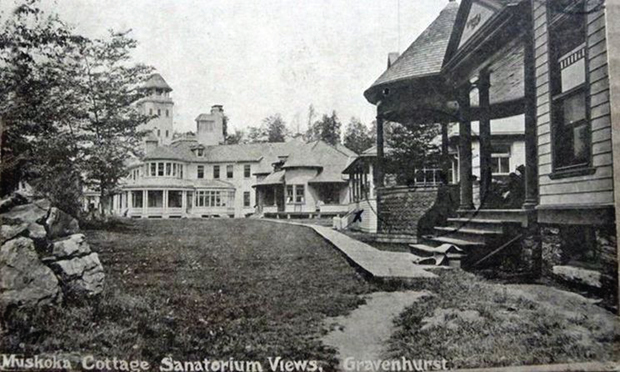

And so, construction began. The Muskoka Cottage Sanitarium was officially opened to great fanfare on August 23, 1897. A special train left Union Station in Toronto early that morning carrying a number of dignitaries and invited guests to the event. After a tour of the facilities, speeches were delivered and thanks were made.

The sanitarium was described thus: Located on the shores of Lake Muskoka, sheltered upon three sides by rocky ranges from 75 to 150 feet high, and has a fine southern exposure. The buildings are of wood with stone foundations and built in the colonial style, painted a pretty green with deep red roofs. The insides are done up in birch hardwood and cement so that they can be thoroughly and regularly washed down. A square tower 130 feet high rises from the centre of the roof and from this tower the fresh air is drawn down into the large air chamber in the basement where, in the winter, it will be heated and distributed to the rooms. The foul air is pumped out of the building by a large fan. There are electric lights, electric bells, plate glass windows in every room, speaking tubes on each floor to the matron’s room and big brick fireplaces in the halls and principal rooms. Laundry chutes are found throughout the building that connect to a disinfecting room where all clothing and linens are sent before being washed. Wide verandas are built both upstairs and down while the roof houses a large platform for sitting and the tower has high balconies with a splendid view of the lake. The building also houses the administrative offices, consulting rooms, drawing room, conservatory, dining room, kitchen, pantry, servant’s apartments and of course, bright cheery bedrooms for the patients. Two notable features were: 1) there were no right angles or corners in the building to prevent a build up of dust and ease of cleaning. 2) Every room is situated at such an angle as to allow sunshine to stream in.

In addition to the main building, there were three cottages nestled among the grounds with large bright parlours and four or six bedrooms. By 1899, five cottages were in operation all due to the generosity of five leading Ontario families. The grounds themselves were said to be universally bright and pretty with handsome stands of ferns, plenty of flower baskets and artistic furniture distributed throughout.

Aside from lots of fresh air and sunshine, good food and moderate exercise, patients were coached on how best manage their illness and prevent the spread to others once they returned home.

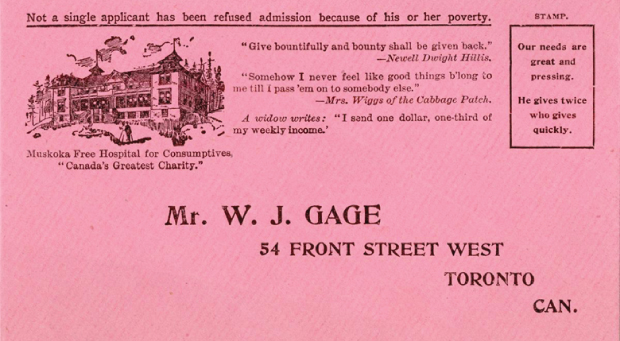

The crowd of dignitaries were well pleased with all that they saw, but acknowledged that once news spread of this place it would be overrun with requests for admittance. Sadly, the available spaces would be wholly inadequate to the need. Furthermore, there was no endowment or fund “that is available for the use of poor patients who are unable to pay even the very moderate fee that is charged at present” (six dollars per week). This hospital was not a “free” hospital. Mr. Gage and his associates at the National Sanitarium Association were unable to secure enough funds to provide respite for the very poor. In addition to this, the sanitarium did not accept advanced or incurable cases. Theses patients were still having to fend for themselves.

Lynne: Was Gage satisfied by this?

Colleen: The answer was decidedly no. He was spurred on to do better.

By 1902, he and the National Sanitarium Association were instrumental in opening the Muskoka Free Hospital for Consumptives. It was constructed a few kilometers away from the Muskoka Cottage Sanitarium. This was, purportedly, the first “free” sanitarium for consumptives in the world. Much less elaborate than the original, it consisted of a single three-story wooden building.

Gage was still not satisfied. What he really wanted was a sanitarium in Toronto, which would be free to those who could not afford to pay even a moderate sum for their upkeep, and he wanted it to be open to well-advanced and incurable cases.

Tired of the red tape involved with establishing a facility in Toronto, Gage purchased the Buttonwood farm, sitting on 40 acres in Weston (about 16 kilometers from downtown Toronto). This was to become the site of the Toronto Free Hospital for the Consumptive Poor. Not only did it require no monetary contribution from its patients, it accepted those with advanced stages of tuberculosis.

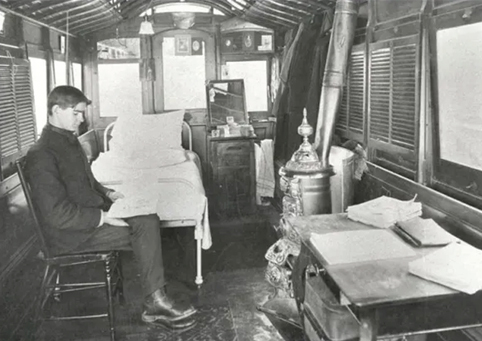

Initially, the sanitarium consisted of the original farmhouse for administrative, medical and common rooms as well as a specially constructed wing to house patients. As time passed and the hospital grew, a separate wooden pavilion was constructed for women patients. Clearly money was tight, so instead of constructing something similar for men, 10 former horse-drawn street cars were moved to the sight and retrofitted to accommodate one or two men each. In addition, wooden shacks were added to the site as needed. It must have been quite a sight, but when the need is great and funds are short, one must get innovative! Later, tramway cars were added, to provide additional space, while the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire raised sufficient funds to build two wards for children and an open air classroom to teach them. By 1907, a training school for nurses was opened on the grounds.

Gage must have been very pleased. In the space of ten short years, there was not one but three sanitariums operating in Ontario.

But then disaster struck - not once but twice. In 1910, a fire destroyed most of the buildings at the Weston site. While insurance covered part of the cost to rebuild, it did not cover it all. The search for benefactors and new funding began. A prominent Toronto couple had lost a daughter to consumption and took on the cause. Mr. and Mrs. R.W. Prittie donated the bulk of the funds needed for a new building. The Prittie Building was opened on the site in 1912, followed by the Queen Mary Hospital for Consumptive Children and the King Edward Sanitorium for paying patients. It must have been a blow to Gage, but very gratifying to see that others were now also dedicating themselves to fighting TB. In recognition of his tireless work, he was made a Knight bachelor and became Sir William James Gage.

The second disaster struck on November 20th, 1920 (and it may have proved too much for him), when the Muskoka Free Hospital burnt to the ground. He died shortly after on the 15th of January, 1921 - of a stroke. The Muskoka Regional Centre replaced the Muskoka Free Hospital in 1923. In honour of his pioneering and relentless work and generosity, the main building of the new hospital was named The Gage.

Lynne: Why are there no sanitoriums today?

Colleen: In 1943, a scientist by the name of Selman Waksman, produced a compound called streptomycin, a type of antibiotic which proved to be very effective in controlling or eliminating TB in patients. You can only imagine that Gage would have been elated at this news. Widespread use began after the end of the Second World War, and was successful in lowering the incidence of TB to levels that eliminated the need for specialized sanitariums.

Lynne: So what happened to Gage’s sanitariums?

Colleen: The Muskoka Free Hospital and Muskoka Cottage Sanitarium were sold to the province; one to be used as a training school for firefighters and the other as a home for developmentally challenged. The hospital on the Weston site is the real success story. Now home to the West Park Healthcare Centre, it is an adult rehabilitation center and provider of complex continuing care and long-term care services. To this day it cares for TB patients and has become renowned for its expertise in treating in respiratory illnesses.

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series