From Serialization to Audible – The Evolution of Reading Fiction

By Colleen Mahoney

I love audiobooks, especially the distraction they offer while doing chores…or on a long road trip. My sister and I recently listened to Tom Hanks (brilliant as always) bring Ann Patchett’s masterpiece “The Dutch House” to life, on a road trip between Toronto and Calgary. The miles flew by.

My assignment is to deliver a brief history of reading…and in reading fiction. But that at least offers a short cut, as reading on its own could take us all the way back to 3500 BCE! Instead, we’re going to move straight past the ancient Sumerians (who developed a rudimentary alphabet) and Gutenberg (who invented the printing press) all the way to the 18th century – when the novel, as a genre, took form…and the 19th when it really took off in popularity.

The Novel

PressBooks (a publishing platform for educators), attributes the rise of the novel to three societal changes:

1. Technological advances in the printing press which made books more affordable and readily available.

2. Increases in literacy rates among working-class men and women leading to more demand for books.

3. And…the fact that authors became dependent on these new reader groups for success and therefore, wrote books they knew would be popular.

So, what would these new readers like? The answer is…stories that they could relate to, featuring middle class characters, or times and places that were familiar. A couple of examples:

- The Soldier’s Wife by G.M.W. Reynolds [1853] is a novel about love and war, set during the Napoleonic era. The story follows the lives of several characters, including a soldier and his wife, as they navigate the turbulent political and social landscape of the time.

- Guy Mannering by Sir Walter Scott [1815] is a tale set in late 18th century Scotland and follows a one-time astrologer who becomes involved in a series of adventures while meeting a vibrant mix of characters from the everyday to the exotic.

While these books may have been more relatable, readers did not lose their appetite for high adventure or the supernatural. A first-rate adventure story, like Treasure Island (Robert Louis Stevenson), a dark tale like Dracula (Bram Stoker) or a gripping detective novel like A Study in Scarlett (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) certainly had people talking and buying.

The novel was believed to have its roots in French romance and many thought they were incompatible with English values. For women, in particular, reading novels was frowned upon, because females were perceived to be easily influenced by books about love and romance and could be led by them to engage in immoral activities.

Serialization

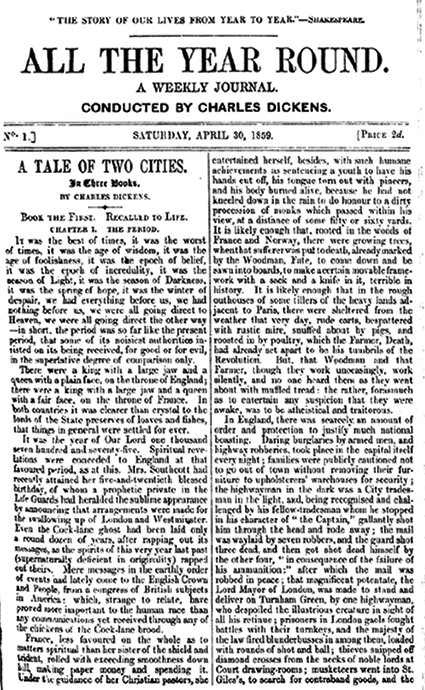

A book was still a luxury that was out of reach for most of the working class in the 18th and 19th centuries. To remedy this, and meet the demand of new readers, newspapers and magazine publishers started printing books in serial form – a much more affordable option. In addition to reaching a larger audience, a publisher could determine the popularity of a story by how many copies it sold. If popular, it would be bound into book format and fetch a greater price. Writers benefited from the steady monthly income, with the added benefit that it grew their fan base. The serialized novel was read then in much the same way a television series is watched now (unless you “binge”). Suspense grows with each installment, until the dramatic conclusion is reached. It was often the case that the regular installment was read aloud by one family member to the others (like an audiobook today).

Serialization began in the 1700’s, but did not really take off until The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (Charles Dickens) was published in 19 installments from 1836 to 1837. In the US, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Harriet Beecher Stowe) was published over a 40-week period starting in 1851, in an abolitionist paper called The National Era. This tradition continued into the 20th century. F. Scott Fitzgerald published Tender is the Night in four installments in Scribner’s Magazine in 1934. Agatha Christie, published many of her novels in The Strand Magazine between 1932 and 1944. In France, Alexandre Dumas was the master of the serial, publishing both The Count of Monte Christo and The Three Musketeers this way.

Over time this practice became so prevalent that most “quality” writers published in serial format and “second-rate” writers were forced to publish in book format. The downside for the author was that he or she had a hard deadline to meet – the public demanded its next installment. If you couldn’t keep up with demand, the newspaper or magazine would drop you from its stable of writers.

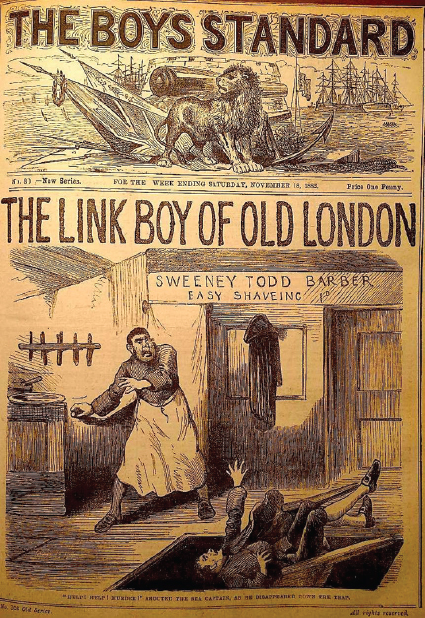

Penny editions, serialized stories of 8 to 10 pages, published weekly (and costing a penny), became wildly popular in the 19th century in the UK. These were less expensive than serials for Charles Dickens’ works (his installments cost 12 pence each). Typically, penny editions were aimed at young working-class men and they evolved into more sensational stories featuring the exploits of detectives or criminals. In North America, the equivalent was “dime-store novels” like Sweeney Todd – going for 5 or 10 cents.

The Paper Back

Steam-powered printing presses saw the rise of the paperback. Of better quality than the dime-store serial, but less expensive to produce than a hardcover book, the paperback also improved the accessibility of novels for the middle-classes. Smaller and lighter (but less resilient to multiple reads), and sometimes referred to as pocket books, they were extremely conducive to travel.

E-Book

The next real revolution in reading, was the e-book format. The idea dates back to the 1930s, when Bob Brown imagined “readies – a simple reading machine, which one could plug into the wall and allow the reader to adjust the type size and avoid paper cuts”. The modern e-book was invented in 1971 by a University of Illinois student, Michael Hart, using a Xerox mainframe computer. He created Project Gutenberg, whose first published e-books included the Bible, the American Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. In 1993, Bibliobytes began to sell e-books online, while Simon and Schuster sold “ibooks”, and Oxford University Press sold e-books through a platform called netLibrary. The problem with these books was that they still required a computer to be read. Though laptops did exist then, most people weren’t taking them to bed (or to the bathtub for a good read with a nice soak).

The answer came when Kindle and Sony developed e-readers in the early 2000s. Finally, e-book readers were not tethered to their computers. Books could be read anytime and anywhere – a beach holiday without having to pack an extra suitcase for books. In 2003, OverDrive, a company which had been digitizing and selling books in “floppy disc” format, used the new “internet” to create a digital lending platform for libraries. One could now borrow digital copies of the latest book and download it directly to an e-reader, tablet, computer or cell phone for goodness sake! Heaven…or so we thought. Enter the audiobook!

Audiobooks

Actually, the audiobook is really not all that new. In 1932, the American Foundation for the Blind built a studio to record books such as Shakespeare’s plays (clunky affairs with about 15 minutes of speech per record). Skip a half century…when Audible launched the digital media player in 1997. The Audible “Player” held about 2 hours (!) of speech, was smaller and lighter-weight than a MP3 player, allowed the user to instantly download books and, most important, allowed for mobility while listening to that book. The gadget was pricey ($200 USD – not including the purchase price of the book). And it was still an extra gadget to carry around. Audible also built a digital library (200,000 titles today).

In the early 2000s came the “smartphone” – a powerful little computer that could do all sorts of things, including storing and playing your favourite music and, yes…your favourite books (in both written and audio format). Overdrive (now Libby) jumped on the bandwagon and enabled libraries to loan audiobooks to their patrons. We can now connect our phones to our car audio system and play books while stuck in traffic or on a road trip. An Audio Publishers Association’s survey found that, overwhelmingly, audiobook users listen in the car, but also while performing everyday tasks such as laundry, exercising, etc.

The Statistics

Today, book-reading is still a popular form of entertainment but the breakdown might surprise you. Fantasy accounted for 16% of all fiction sales, suspense, thriller, mystery and detective came in at 14%, general fiction 13% and romance 12%. Print book sales are still booming with all ages, but e-books seem to be most popular with older generations. The audiobook’s popularity climbs every year. As companies like Audible engage more celebrities (I really do love Tom Hanks) to read classic and new books, I predict this will continue!

To Order Your Copies

of Lynne Golding's Beneath the Alders Series