While I did all of the initial research for my Beneath the Alders series and for the first book in the series, The Innocent, I was greatly assisted in completing The Beleaguered and The Mending by the research skills of my good friend Colleen Mahoney, a pre-maturely retired librarian. In this article, Colleen answered specific questions I posed about European travel in the post World War 1 period.

Lynne: We know that recreational travel to Europe greatly increased in the early 1920s? What was travel to Europe like prior to the 1920’s?

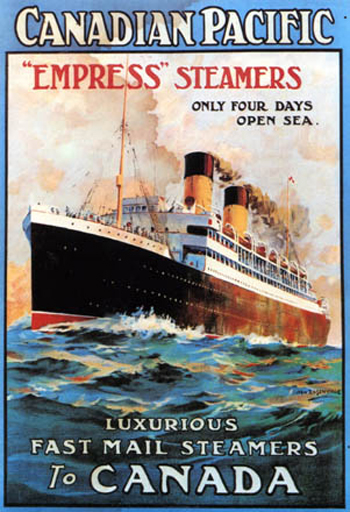

Colleen: In the late 1800 and early 1900s, the transatlantic passenger trade became a highly profitable and competitive business. Cargo ships (of evolving type and increasing capacity) had plied the seas in great numbers for hundreds of years and passenger ships certainly were around - but never before in the numbers they were during this time period. Immigration was the greatest driver for this change, as more and more immigrants began to cross the Atlantic for a better life in “America”. As a result, new shipping companies were born (Cunard and White Star, for example) and companies that previously concentrated on shipping cargo introduced passenger ships into their fleets (Canadian Pacific would be a great example of this).

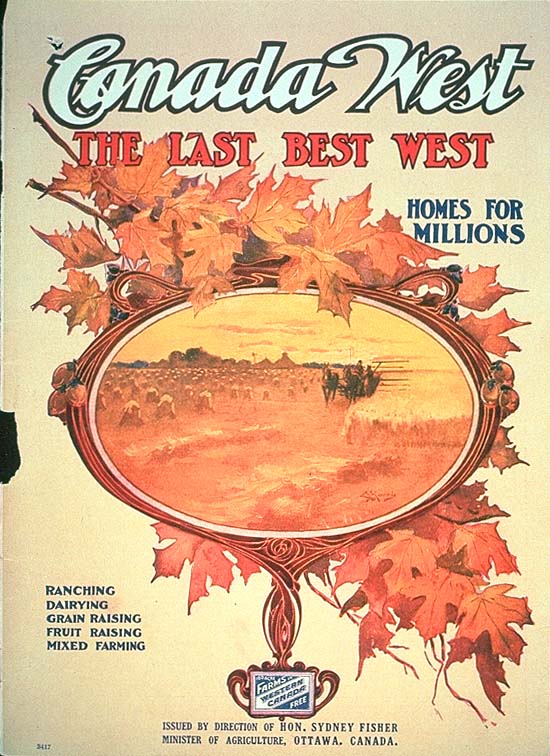

The governments of Canada and the United States actively recruited immigrants from across Europe to help fuel their economies and occupy their vast “unsettled” lands. During this period, anywhere from 63,000 to 133,000 immigrants arrived each year in Canada. In the early 1900s the Canadian government used advertising campaigns to attract Europeans to populate the West and develop a new agricultural sector on the prairies. More than 400,000 immigrants arrived in 1913 alone.

In the States, the numbers were even more dramatic. Immigrants fleeing poverty, famine and repressive governments saw America as the “land of opportunity” - a place in which it was possible to own land and build a comfortable life for themselves and their families. Between the years of 1880 and 1920, the United States welcomed about 20 million immigrants – the peak year being 1907 with 1.3 million.

But sadly, as we still see today, with increased immigration, often comes prejudice and nativism. Anti-immigration sentiment increased dramatically after the World War I. As a result of an economic downturn from 1918 to 1921, soldiers returning home from Europe and newer Canadians or Americans competed for scarce jobs.

By the end of this period, governments were under pressure to dramatically stem the flow of immigrants arriving each year. The relatively relaxed immigration laws that existed in both countries began to change. Legislation was introduced that restricted the regions from which immigrants could come. Asian immigrants, for instance, were almost banned outright. And new requirements, such as literacy and immigration fees, resulted in only the better educated and wealthier person being eligible to legally immigrate.

By the 1920s, the steady surge of immigrants began to ebb contributing to a decline in the profits of the shipping companies.

Lynne: So what happened to the shipping companies?

Colleen: Several things happened at the turn of the 20th century that had an effect on the evolution of passenger ship travel. Society in North America was changing. Standardized work weeks were introduced, allowing for more leisure time. Labour movements resulted in better wages for the middle class. And banks began to introduce favourable credit plans.

While the North American economies recovered relatively quickly from the downturn immediately following the World War I, the economies of European countries continued to struggle. Cities, towns and farmland lay in ruins. France’s industrial heartland was almost destroyed by the relentless military campaigns. Europe was straining to rebuild when so much of its able-bodied workforce had been either lost or incapacitated.

The United States and Canada seized the opportunity to fill the production gaps. Demand for Canadian goods soared as the manufacturing sector boomed in Canada and the US. Pulp and paper, lead, zinc, silver and copper were used to produce consumer goods such as radios, cars and home appliances. Wheat, meat, cheese and other staples were exported to Europe as those countries began the process of rebuilding their agricultural sector. By the mid 1920s, many North Americans found themselves with disposable income and leisure time for the first time in their lives.

I also should mention the psychological effect of the war. It was long. It was bloody. And it was devasting to many families on both sides of the Atlantic. The 1920s ushered in an era of hope and new possibilities. People were open to new adventures. The Roaring Twenties began.

Enter the shipping companies. Fewer immigrants resulted in ships crossing the Atlantic at less than capacity. The increasing wealth of the middle class presented the perfect opportunity to fill them. While the mainly immigrant third class steerage ticket still existed, the tourist class ticket was introduced.

The accommodations in tourist class were obviously not as luxurious as the first class shown in movies. Staterooms were smaller but still well-appointed, with sleeping capacity for four people. The dining saloons were far less opulent but still provided very good food. And to complement these, there were lounges, nurseries, gymnasiums, and smoking rooms. On board activities were abundant and varied. Slogans began to appear like “It’s not the destination but the journey” or “The best part is getting there”.

The shipping companies were not the only ones to pivot to the growing travel industry. Travel agencies sprang up everywhere. Agencies would sell return passenger ship tickets, arrange for accommodations in Europe and provide a tour guide that would take care of transportation between destinations, provide for guided tours of attractions, museums, etc., and help to bridge any language barriers that existed. It was a largely hassle-free and relaxing experience at a relatively affordable price.

Lynne: Cruises are still a popular vacation option but do people still travel to Europe by ship?

Colleen: For the most part no, because air travel has cut down dramatically on the amount of time it takes to get to overseas destinations. That being said, some cruise lines will offer lower price Atlantic crossings when they are moving their ships between different areas of the world at the end of each season. For instance, the Mediterranean is a popular destination in the summer but not in the winter, so cruise lines will often move their ships from Europe to a warmer climate, for example the Caribbean, for the winter.

One other fun point…It’s interesting to note that winter cruises to warmer climates became quite popular in the 1920 as well, so much so that sporting tanned skin in the winter became a status symbol.

Lynne: How is European travel similar today? Do people generally visit the same places, see the same things?

Colleen: Yes and no. A lot has changed since 1926. The most obvious difference is of course the decline of travel by ship and the ease of air travel. The Melita, Mountnairn and other ships of that vintage took an average of 5 to 7 days to cross the Atlantic. By contrast, a flight to Europe from North America will take anywhere from 7 to 12 hours depending on where you are starting from or going to. The speed afforded by air travel has also opened up further, more exotic, destinations to Canadians. Asia, South America and Africa are very popular especially among the younger set.

The travel agency has almost been replaced by on-line travel sites. With a few clicks, travellers can book a flight or hotel rooms. Paid Instagram “influencers” advise where to go and what to see while there. Downloading Google Maps to our phones means it’s almost impossible to get lost and language translation apps relieve the stress of interacting in a foreign country.

That being said, Europe is still a very popular destination. Approximately, six million Canadian visited Europe in 2019. The Euromonitor International Report into the Top 100 City Destinations listed London as the most visited city for many years running. Following a close second was Paris. After that it was Istanbul, Antalya (also Turkey), Rome, Prague, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Vienna and Berlin.

A quick scan of newspapers in the 1920s shows that European travellers from North America tended to frequent Great Britain (from London to Glasgow), as well as Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy and France. I would have to guess the popularity of Eastern European destinations now is due to the ease and speed of air travel. In the 1920s, boats were likely to arrive in a port of Britain or France. Travel to various countries following this would have been chiefly by train. Time constraints likely would have been a big factor in determining which other countries could be visited.

Once tourists are in cities like Paris or France, the sites visited have not varied much from the 1920s. The Louvre, Eiffel Tower and Notre Dame Cathedral are still the most visited sites in Paris. Buckingham Palace, the Tower of London and the British Museum are the most frequented in London.

Lynne: What else did you find interesting about this era of travel?

Colleen: What I found really interesting when researching this subject were the stunning posters advertising ocean travel. At the time, Art Deco was the dominant style of architecture and design and it influenced almost every product in life in the 1920s including buildings, art, furniture and yes, even the décor on ocean liners. It was characterized by bright colours and bold geometry and was meant to convey a sense of power and modernity.

In addition, railway and shipping companies commissioned well-known artists to create posters in the Art Deco style to advertise their voyages.

One such poster, entitled L’Atlantique (see above), recently sold at auction for more than $50,000 Cdn.

To Order Your Copy of

The Mending

select one of these links.