ARTICLE 3: RAILWAY FEVER

These days as railway lines fall into disuse, as their ties rot and their rails are lifted, as their paths are converted to hiking trails, we forget the role that those steel rails played not only in transporting Canadian people and goods, but in the formation of Canada itself and hundreds of towns and cities within it.

In 1867, the Grand Trunk Railway was the longest rail line in the world connecting Quebec and Ontario to Portland, Maine and other New England states. The line itself crossed the St. Lawrence River at Montreal via the Victoria Bridge which opened to much acclaim in 1860. Although the line was located in North America, the financing to build the line originated mostly in England, the location of its head office.

It was the promise of the Intercolonial Railway line connecting the colonies of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to the Grand Trunk Railway in Quebec that helped convince delegates from those colonies at the 1864 Charlottetown conference to join the two Canadian colonies in a single Dominion.

Later a similar promise, fulfilled by the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway that connected the four eastern provinces with those in the west, enticed British Columbia to join confederation. Prince Edward Island joined the Dominion in part due to the promise of the expanding country to assume the debt PEI had incurred in building its railway.

Railways were popular not only because they could move people from one place to another—including immigrants settling the west-- but also because they could move goods from one market to another. It was the knowledge that Canadian goods could be transported from one Canadian market to another that allowed the government in 1878 to adopt a tariff policy against imported goods.

The promise of a railway line could make a government. It could also defeat a government. The circumstances in which Sir Hugh Allan won the contract to build the CPR led to the Pacific Scandal and the resignation of John A Macdonald’s government in 1873.

Governments at all levels invested in railway lines because of the prosperity they promised. In addition to allowing goods to be transported, railway depots or stations allowed for the development of villages, towns and cities including the hotels and telegraph services located within them.

Two statutes accelerated the construction of and investment and speculation in railway lines in the Province of Canada. The first of the two was the Guarantee Act, 1849, pursuant to which the government agreed to guarantee the interest of half of a company’s bonds as soon as it had completed construction of half of a track at least 75 miles long. The second was the Municipal Loans Act, 1852 which allowed municipalities to make loans to railway companies. Although the two statutes increased investment in railway endeavours and prosperity for some, they caused the economic ruin of others. (1) See the situation in Peel County, as described in The Mending for an example of this.

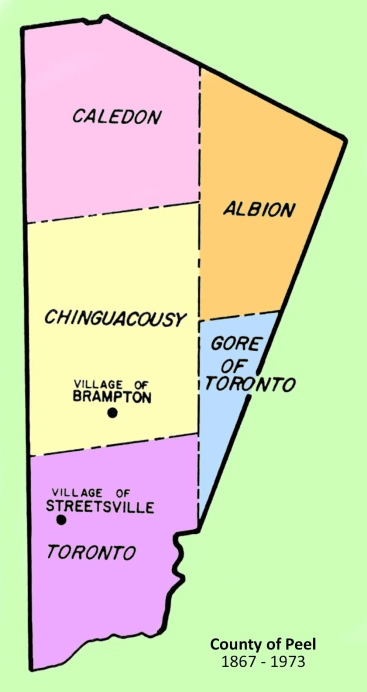

In 1851, Chinguacousy, the township in which Brampton was located, agreed to purchase £10,000 of securities in the Toronto and Guelph Railway company on the condition that its rails ran through Brampton and that a station be located within it.

Map compliments of the Peel Archives.

It was a good investment. The line which connected Brampton on an east west basis to Toronto and points beyond had barely opened when the Toronto & Guelph was purchased by the Grand Trunk Railway Company and the debenture issued to Brampton was repaid in full.

Not all rail investments were as successful. In 1879, thirteen years after the Toronto & Guelph line opened through Brampton, rails for a second line were laid through Brampton. This line that ran through Brampton on a north south basis, the Credit Valley rail line, was built with funds invested in part by governments but largely with funds of private citizens hoping to make the return that the township and many others had made on their investment in the Toronto and Guelph.

In this they were greatly disappointed. From its earliest days, the line was in financial disarray. Reports abounded regarding the number of times trains on the Credit Valley sat motionless waiting until funds could be obtained to purchase coal from the line’s competitor, the Grand Trunk Railway. With barely enough money to buy coal for its locomotives, there were certainly no funds to pay dividends to shareholders—let alone to redeem their shares.

Eventually the Credit Valley rail line was assumed by the Canadian Pacific Railway company but it was never as viable as the east west Grand Trunk line. In 1981, its station on Queen Street in Brampton was closed and moved to Huttonville for use in a nursery business.

Fortunes were lost on the Credit Valley rail line, as they were 50 years later on the Grand Trunk line. After several expansions, that line went into bankruptcy. (Recall the Earl of Grantham in Downton Abby.) The line through Brampton was assumed by the Canadian National Railway company, who owns it to this day.

What does this have to do with the Presbyterian Church in Brampton and why the fictional Stephens family in my Beneath the Alders series cannot enter it? You’ll have to read The Mending (out May 2021) to see.

(1) For more on this see:Collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/scripts/explore.php?Lang=1&tableid=11&tablename=theme&elementid=4__true&contentlongRailways in Canada, 1830-1918 By Ève Préfontaine

To Pre-Order Your Copy of

The Mending

select one of these links.