While I did all of the initial research for my Beneath the Alders series and for the first book in the series, The Innocent, I was greatly assisted in completing The Beleaguered and The Mending by the research skills of my good friend Colleen Mahoney, a pre-maturely retired librarian. In this article, Colleen answered specific questions I posed about Hurricane Hazel.

Lynne: What made Hurricane Hazel unusual?

Colleen: Hazel was the deadliest and costliest hurricane of the 1954 season. First spotted in the Windward Islands on October 5th,, it began moving west over the Caribbean Sea increasing in intensity as it went. By October 9th Hazel was classified as a category 4 storm meaning that it had sustained winds of 209 kph to 251 kph. For seven days Hazel moved northeast passing over Haiti on October 11th with deadly results (400 to 1000 estimated dead) and over the Bahamas on the 13th of October killing six people. When Hazel made landfall in the Carolinas on October 15, 1954, it was still classified as a Category 4 hurricane with winds recorded as high as 240 kph. A storm surge of over twelve feet devastated the coast line and reached as high as eighteen feet at Calabash nearly destroying Garden City, S.C.

Hazel rapidly moved inland and northward over Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, Washington, D.C., and New York with wind gust reported from 125 to 180 kph. Hurricane Hazel claimed ninety-five American lives and caused $308 million in damages (about $3 billion in today’s dollars) before moving into Ontario.

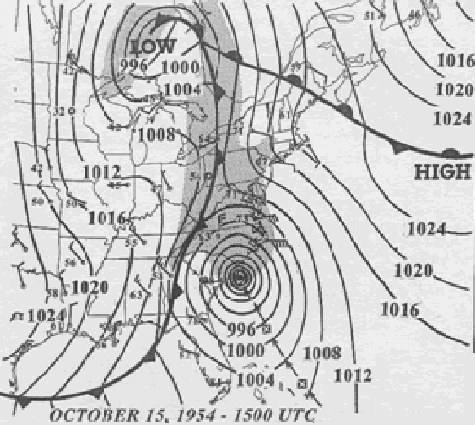

While Hazel was an unusually strong hurricane, up until this point, there was nothing particularly unusual about its behaviour: It followed a path that was not unusual and it was weakening and breaking up as it moved over land. However, that was about to change.

As the remnants of Hazel moved into Western Ontario, it collided with a cold front moving eastward from the Rocky Mountains, rapidly causing it to re-intensify into an extra tropical cyclone. As one reporter put it, “it was like fuel fed to dying fire at just the right time”. Some scientists refer to this newly formed storm as Hazel II. It was this extra tropical cyclone that was about to unleash its fury on Southern Ontario.

Lynne: What made Hurricane Hazel so destructive?

Colleen: Firstly, Hazel dropped record amounts of rain – anywhere from 76 to 214 mm were recorded depending upon where it fell. Additionally, the summer and fall of 1954 had been particularly wet in Southern Ontario and it had been raining for three days prior to the storm, causing the ground to be completely saturated before Hazel hit. Rainfall associated with Hazel could not be absorbed into the ground so it began to fill local streams and rivers and finally spilled over into the floodplains. The Highland Creek, Humber River, Don River, Etobicoke Creek, Credit River and 16 Mile Creek all overflowed their banks.

Courtesy of Toronto Public Library

Secondly, the region was unprepared for a storm of the magnitude of Hazel. It was believed by many meteorologists that Hazel would dissipate over the Allegheny Mountains and would be a “weather event” but nothing too out of the ordinary. The weather office issued a bulletin at 9 o’clock pm on October 16 saying that the intensity of the storm had decreased to the point where it was no longer considered a hurricane and that the weakening storm would pass east of Toronto before midnight. The city could expect rain and winds of 64-80 kph. In reality, wind speeds averaged 110 kpm, but gusted up to about 160 mph.

Other meteorologists were keeping their eye on the cold front coming from the west and predicted that the rain associated with Hazel could be the heaviest ever recorded in Toronto’s history. This message was not widely disseminated and most people had no reason to take precautions, leaving much of the area unprepared for what was to come.

Thirdly, the floodplains of many of the creeks and rivers mentioned above, were populated with family homes. These families were used to flooding and many were prepared to deal with water in the basement. It was only when the rivers and creeks grew to dangerous levels that some decided to move to higher ground. Others had already retired for the night and were unaware of just how dangerous the situation was becoming. Raymore Drive in Toronto’s west end was particularly hard hit. It was situated on the banks of the Humber River. A bridge was partially washed out by the driving river but instead of washing downstream towards Lake Ontario, the bridge held at one end and directed the water towards Raymore Drive. The Humber smashed into the houses and swept them away, many still occupied. Thirty-two people died on Raymore Drive alone and another sixty families were left homeless.

By the time Hazel had finished with southern Ontario and moved off towards Timmons and out over James Bay, it had claimed the lives of eighty-one people, and left 4000 homeless. Heavy rain and high winds washed out bridges and roads, completely destroyed many homes and buildings, flooded underpasses and houses, uprooted trees, killed livestock, knocked buildings off their foundations, tossed planes around the Island Airport and derailed two passenger trains. It is estimated to have caused about $25 million in short term damages (almost $250 million in 2021). Long term damage including lost property, recovery costs and economic disruption was estimated at over $137 million ($1.34 billion in 2021).

Lynne: How was Brampton affected by Hazel?

Colleen: Brampton had one of the highest recorded rainfalls anywhere that night with 90 mm falling between 9 o’clock pm and midnight. But if you factor in the previous forty-eight hours, about 210 mm fell. Some believe that had the Etobicoke Creek not been previously diverted, the downtown area of Brampton would have been wiped out.

As the recovery effort got underway, Brampton man, J. E. Houck, auctioned a Holstein heifer he named “Flood Relief”. Flood Relief raised $2000 as, each time it was sold, the money raised was donated and the heifer was put back on the auction block. This happened fifteen times before Brigham Young University in Utah paid $385 in the final bid.

Lynne: Disasters seem to bring out the best people. Was that true in this case?

Colleen: There is no end to the stories of heroism that night and in the following days. Fire fighters, policemen and other emergency workers were out in full force. Many were occupied rescuing people from stranded cars, from trees where they had climbed to escape the rising waters and from the tops of roofs where they had climbed once the waters had flooded their homes. Unfortunately, five firemen were drowned when their own vehicle became stranded and the water began moving it downstream.

I should mention that most of the area’s citizens went to bed that night with no idea that, along the rivers and creeks, there were literally hundreds of people fighting for their lives. Of those that were aware that a crisis situation was building, many came to help where they could.

North York Police Constable Jim Crawford and contractor Herb Jones, took Jones’ small boat out on to the Humber River where they motored from house to house pulling people off porches and roofs and out of trees. They are credited with saving between fifty and sixty lives that night. Neighbors went door to door in waist high water warning sleeping residents of the danger and helping them to higher ground. Others stood guard at washed out bridges to ensure that no vehicles drove into the rivers.

Legions, schools and churches opened their doors to act as emergency fire stations, health units, cafeterias and, unfortunately, morgues. Citizens from across Toronto donated clothing, blankets and other necessities. A convoy of twenty-eight trucks travelled from Toronto to Holland Marsh with relief supplies on Saturday, October 16th. The CNR station in Bradford set up several Pullman cars as temporary housing for Holland Marsh families who found themselves homeless.

Local churches, service clubs and civic groups swung into action with recovery efforts. As it happened, the Salvation Army was holding a Congress meeting that fateful weekend. They quickly deployed mobile canteens which circulated in the flood-stricken areas, offering food, blankets and clothing to victims and rescuers. In the following days, they helped family members identify bodies of their loved ones and even attended funeral services with them.

The military was bought in to conduct ground and air searches for bodies, pump out swamped land and clear the debris from destroyed buildings and trees and other obstacles blocking rivers and creeks.

The Salvation Army set up donation bubbles (like the ones you see at Christmas) up and down Yonge Street asking for donations for flood victims. Men and women of the Salvation Army rang their bells and asked Torontonians to give what they could. The bubbles stayed in place through Halloween.

Cash donations came not only from the city but across the country: the Ford Motor Company, CHCH-TV in Hamilton, Algoma Steel, Canada Steamship Lines, Consumers’ Glass Co, Laura Secord, John Labatt, United Church of Canada, the Kinsman Clubs of Canada, the Mayor of Windsor, the City of Winnipeg were among those who gave generous donations.

Lynne: What else was really interesting?

Colleen: I’m glad you asked. This is an astonishing story. The de Peuter family had recently immigrated to Canada and settled into the Holland Marsh area to farm. The Holland Marsh area was particularly hard hit with flooding and high wind. Mr. and Mrs. De Peuter, their twelve children and a neighborhood boy were in the house that night when wind and water knocked the house off its foundation and it began to float. The fifteen occupants scrambled to the second floor. As the house began to tilt one way or the other, they ran from one end to another to keep it on an even keel. The three youngest children became violently seasick. Along the way they rescued a soldier by throwing a blanket to him from a bedroom window. Five hours after their voyage began, the house finally came to rest about five miles from its foundation against the shoulder of Highway 400.

Lynne: What changes were put in place after the Hurricane to prevent similar damage?

Colleen: The City of Toronto established the Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (MTRCA) to study the causes of Hazel’s devastation and recommend changes to avoid a repeat in the future. The Authority appropriated great swaths of land particularly in the floodplains of the Humber Valley and converted it to parkland, golf courses or agricultural land

The United Nations World Meteorological Organization retired the name Hazel from the list of potential names. There will never be another Hurricane Hazel.

To Order Your Copy of

The Mending

select one of these links.