The Mighty Etobicoke

London has the Thames, Paris the Seine, Strasbourg, the Rhine. Brampton has the… Etobicoke. If you are thinking that Brampton’s little creek does not compare with the big rivers of those metropolises, you are right! Certainly, there is no comparison in terms of the way those waterways contributed to the commerce of the cities around them. The Etobicoke Creek offered no ports, not being wide or deep enough to host any seaworthy vessel. As for mills, in Brampton the creek only ever powered one: for a time the grain processing mill for John Scott’s distillery. No, the power of the Etobicoke Creek in Brampton was not in what it allowed to be constructed but rather in what it caused to destructed.

The creek, which emanated in the Caledon hills, led a fairly docile existence as it travelled south to empty into Lake Ontario--docile that is until it sidled up to the old Hurontario trail in the area that came to be known as Brampton. The problem was that both the creek and the inhabitants liked that trail. The creek liked it so much that it zigged and zagged across it, in order to appreciate its many different prospects The business people and residents, well they liked it because for the longest time the trail was the only–and even then not always—reliable road.

The people and the creek could have shared the road and lived in some equanimity if it were not for the other activities in which the pioneers were then engaged. In order to gain full title to their land, settlors in Chinguacousy Township (the geographic area in which Brampton was located) were clearing their land. As they cut down trees and as they drained or filled the area’s marshy areas, they left the creek with nowhere to pool when rains were heavy or the spring run-off began. The water moved down hill, towards Lake Ontario and Brampton in between. At those times, the little creek grew, its strength surged. Torrents of water pushed into Brampton where it found a temporary home: the premises of businesses built along the main street, basements of homes built nearby, public school grounds, athletic fields, and the very road itself, sometimes to a height of five feet above road level.

Suffice it to say these floods caused thousands of dollars of damage (millions in today’s dollars). And these were only the great floods. Floods of smaller proportions and their attendant costs and even resulting losses of life were also experienced by Bramptonians. It came to an end in 1952 when the creek’s path was diverted. But why did that diversion not occur before then? What did the inhabitants do to try and avoid the mayhem caused by the creek?

They ignored the Creek

The arriving Brampton settlers first tried to ignore the creek. They treated it gently, walking through it where it was quite shallow and installing foot bridges where it was more voluminous. The creek respected these gentle measures until 1854, when on May 2, the downtown area was engulfed in water. More substantial bridges were erected.

In August 1857, these measures were found to be futile when after a day and a half of torrential August rains, the town was left under five feet of water, the planks of its roads and sidewalks upturned, a building toppled and the small and bigger bridges swept away.

Brampton residents it seemed, dusted off (or wrung out) their sleeves and rebuilt the fallen structures—except for the planked roads. That was an experiment deemed not worth repeating. Perhaps the inhabitants thought that the flood was a once (or twice) in a century event. If so, they were soon proved wrong.

A flood in September 1873 following a few days of “moderate rain” left one foot of water in the stores along Main Street and caused $200,000 of damage. People and their possessions had to be rescued by boat. Another flood in 1878 was so great that those intending to vote in an election held that day had to be transported to the polls by boat or raft.

They caged the Creek

By this point it was realized that something more needed to be done. The notion of burying the creek was presumably ruled out for the town’s people turned in another direction. Instead of burying the creek, in the early 1870’s they chose to raise the roads. It is possibly a good thing that to this point Brampton’s four corners area was only beginning its ascendance as a commercial core. It is hard for us to imagine now, what would have been involved in building these caverns and raising the street level of Brampton by eight feet but it would have been harder if there were more buildings to be lifted.

The raised roads allowed the creek to run mostly unimpeded under Main Street from the area just south of the Grand Trunk (now CNR) railway tracks in the north, to a point just across from St. Paul’s church in the south, where it emerged running through parklands parallel to Main Street to the east, before crossing to the east side of Main at Wellington.

The raised roads were a vast improvement. They prevented major flooding following an ordinary downpour. However, the below-street level conduits could not contain the creek following a big spring run off or a flood level storm, such as the one that occurred on Christmas Day in 1893. That storm plunged the town into not just water, which rose five feet above street level, but also into darkness following the flooding of the local gas works and electrical system.

The deluge in 1948 was even worse. Breaking all records, it saw Brampton flooded with six feet of water and even resulted in train disruption. The problem could be ignored no longer.

They diverted the Creek

At times like this, talk turned to diverting the creek –changing its course. This talk was not new. Brampton leaders had been ruminating about it since the 1860’s. In 1873, Brampton was the subject of two acts of the provincial legislature. The first provided for Brampton to shed its status as a village and to be reincorporated as a town. The second approved the construction of the diversion.

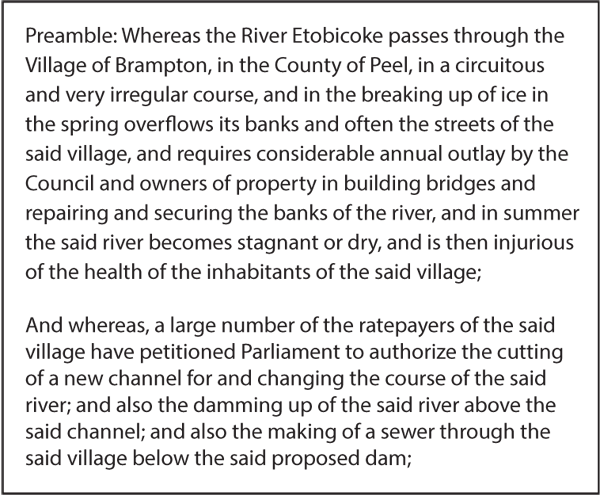

The preamble of the Act includes the following:

The Act was passed into law but nothing came of it. Although the costs of annual flooding were considerable, the costs of completing the diversion were astronomical and the responsibility as between the town, the County of Peel and the province could not be agreed.

Calls for a diversion were renewed following each major flood but, like the creek itself, they receded at other times. Indeed the reporting on the annual floods was almost common place. On March 9, 1922, the Conservator, the local Brampton newspaper, reported simply that the banks of the Etobicoke had again overflown. No particular damage had been done, but it had been necessary again to break up with dynamite the masses of ice blocked at the Wellington Street bridge. The ice was holding back masses of water which was flooding onto the streets and nearby park.

The stress on that bridge at Wellington Street and on two others on Main Street within the town’s confines, were part of the issue in assessing the costs of the diversion. The diversion involved not just the re-routing of the creek, but the removal of the bridges that crossed it, the reconstruction of the road next to which the Etobicoke had run and the costs of the retaining walls. In 1922, the provincial government offered to pay forty percent of the costs to repair the centre twenty feet of the road and the Wellington Street bridge and the bridge to the south, but it would not pay anything towards the retaining walls or the costs to repair the balance of the road and bridges.

The stalemate might have continued had it not been for the 1948 flood. Fortunately, by that time serious plans had begun to divert the creek. Two years earlier, in 1946, the Etobicoke-Mimico Conservation Authority had been formed. Included among its members was Brampton mayor, John S. Beck. Among the first tasks undertaken by the authority was the investigation of the means of controlling the creek as it ran through Brampton. The plan faced the usual opposition by some—the costs could not be borne in their entirety by Bramptonians. But this time the voices of those calling for the diversion and the funds to see it built were sufficient for the plan to come to fruition.

In 1952, with the skills and talents of Dr. Ross Lord, Head of the Mechanical Engineering Department of the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering at the University of Toronto, who developed the plan, the Toronto engineering firm of James Maclaren Associates that directed the work and the physical construction undertaken by the Brampton Armstrong Brothers Construction firm, the creek was at long last diverted. A 2,500 foot open cut concrete channel was laid on the east side of Brampton’s downtown area starting just north of Church Street running south where it rejoined the existing creek route near what is now the Brampton Mall. Concrete bridges were built over the channel. The big Wellington Street bridge was removed as well as the bridge to the south. Main Street was repaired and widened. The entire cost was $1,000,000, of which the province paid seventy-five percent.

The creek was moved just in time. Had it continued to run in its old bed, it would have destroyed Brampton’s downtown in the 1954 hurricane named Hazel.

To Order Your Copy of

The Mending

select one of these links.