Demobilization: A Logistical Challenge for our Times

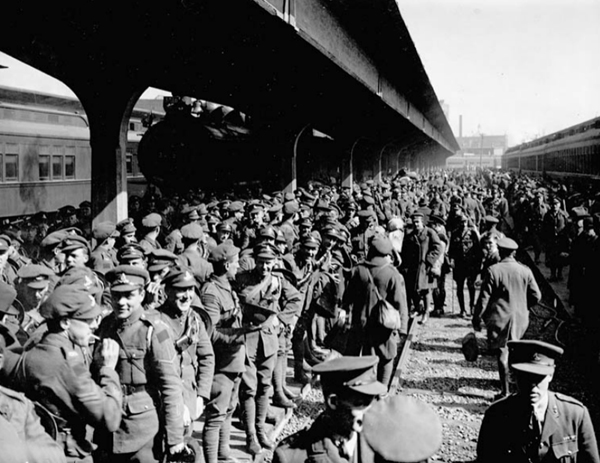

In The Mending, as in real life, our protagonist Jessie waits for male friends and family to return to Canada following the armistice. On November 11, 1918, there were 270,000 members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force overseas. Some of those members would be required to stay in Europe a little longer, taking an occupation role in Germany until early in 1919. The rest could have immediately returned home, if only it was physically possible to do so. Returning those 270,000 troops as well as 37,000 dependents to Canada constituted the largest movement of Canadians up to that time. It was also one of the largest logistical challenges faced by the government.

Reading about the demobilization process, I was struck by the similarity of some of their logistical challenges, with the greatest logistical challenge of our time: securing and dispensing vaccines to Canadians. Maybe you will see those similarities too.

Not Quite Prepared [Enough said]

By August 1918, the tide of the Great War had turned in favour of Great Britain and her allies. Rumours of an armistice had circulated in Canada in the weeks and months before its ultimate declaration in November 1918. Yet the government was not prepared for the war’s end and the return of our troops.

Canada had some experience in returning men home. By November 1917, Canadian hospital ships were bringing home 2,000 men a month. But key decisions about how a mass demobilization would occur had not been made.

The Sheer Numbers [The entire world needs vaccines]

Three hundred and seven thousand people is a lot of people to transport. They all had to be returned by ship. To put this in perspective, the SS Montnairn, an ocean liner that Jessie and her family took home from Europe in 1926 could accommodate 2,000 passengers. At that rate, and assuming that ocean liners of that size were used for the purpose, it would take 154 crossings to get the Canadians home.

Of course, Canada was not the only country seeking to bring home its troops and their dependents. At the end of the war, New Zealand had more than 56,000 service people overseas; Australia, 170,000; South Africa, 37,000; and the United States, 1.5 million.

The Americans and Australians confiscated and retrofitted a number of German ships for the purpose, including in the case of the Americans, the SS Prinz Friedrich Wilhelm which was eventually renamed the SS Montnairn, referred to above. Even so, there were simply not enough ships available to return all of the troops at once. Ports, dock space and British and European rail capacity also had to be considered and regulated.

In the end it was determined that Canada could transport home 50,000 people per month.

From what country should they depart? [Moderna, AstraZeneca or Pfizer?]

The next question was: from which country should the troops depart? Most Canadian troops were in France at the end of the war. But many had friends and relatives in Britain that they wanted to see before they left for home. The prospect of so many troops travelling to Britain and back to France (with their dependents) before disembarking for Canada was not attractive in part because the British needed rail and shipping resources for their own troops –not just those troops returning to Britain but also to support those who would be returning to the continent to support the occupation efforts in Germany.

When the repatriation plans were complete in January 1919, they reflected the decision to have the troops depart for Canada from Britain. After leaving France, the troops would hold in Bramshott or Whitley, England to get their documentation in order (estimate three days). They would then have two weeks leave in England. At the conclusion of the leave they would reassemble at one of eleven camps where they would wait before being sent to Kimnel. At Kimnel they would hold for a further week or ten days before departing for Canada from Liverpool. At least that was the general plan. In fact troops sometimes held for six weeks or more at Kimnel and some left from other ports such as Southhampton.

Priority [Who will be vaccinated first?]

A further question arose as to who should first be returned home. The troops supported a “first over, first back” policy, with pride of place going to those who had served the longest.

That proposal had a number of drawbacks including the fact that those with the longest service included clerks, cooks and the like, given their non-combative roles. Who would tend to the administrative and more basic needs of those remaining if the clerks and cooks returned home first?

The federal government favoured a policy whereby men returned based on economic and employment priorities. This option was supported by employers, organized labour and even the Great War Veterans Association.

But General Arthur Currie, the commander of the Canadian corps, wanted the troops to return home in their units. In addition to being more efficient he argued that it would better maintain discipline while the troops were overseas and allow units disembarking in Canada to be properly welcomed by their communities.

In the end, General Currie proposed a compromise. The troops would return in two separate streams. One hundred thousand men in major combat units would return home in their units, under the command of their own officer. The remainder would be reorganized into “drafts” based on their locality and length of service. Within those drafts, married men would have priority, at least in part, because it cost the government more to keep married men in service than unmarried men.

In January 1919, this became government policy but not before a number of soldiers in training camps – men who had absolutely no front line service, men who certainly fell into the group of the last over– had made their way home.

Those at home played a part [The provinces are responsible for distribution and injections]

Other logistical issues played a part. Spanish flu, which reached its apex in England in November 1918, had returned again in January 1919. That winter was particularly cold. The combination of sickness and cold weather created a shortage of coal. Rail workers and others struck. The use of the rail lines had to be rationed. The transport of Canadians from their camps to the shipping ports was not initially a priority. But the logistical issues were not all on the eastern side of the Atlantic.

Circumstances at home contributed to the timely movement of the troops and their dependents. First of all, Canada only had two Atlantic ports that were able to receive ocean liners and other large ships in the winter months: Halifax and St. John. Halifax had not fully recovered from the massive explosion of December 1917.

In addition, once the troops arrived on the east coast they had to be transported by train to provinces across the country. The maximum number of troops and dependents that the Intercolonial and Canadian Pacific railway companies could transport out of the Atlantic region per month was 30,000 --just over half the number that the government planned to bring home. The number would increase once the ice melted and the St. Lawrence was navigable. Quebec City and Montreal offered additional port and rail capacity.

Finally, the good intentions of Canadians played a role—a reminder of the law of unintended consequences. The situation arose from the poor conditions of one of the first ships to return our troops. The SS Northland arrived in Halifax harbour on Christmas night 1918. Reporters attended in abundance to capture the smiling faces of our returned heroes. After waiting in quarantine off the coast of Halifax for a day, the soldiers disembarked fit to be tied. There had not been enough food on the ship. What had been served was cold and unappetizing. Stewards illegally sold food to hungry passengers. For the entire voyage, all of the troops except for the officers were required to stay below decks where the conditions were unsanitary.

Canadians were outraged. Wanting to avoid such censure again, the Canadian government required all future ships transporting our troops to be equipped to a higher standard. While the gesture was well meaning, the result was that the return of our troops was further delayed as ships that could otherwise have taken them—ships that were perfectly seaworthy—were deemed unfit and could not be used until properly retrofitted.

Stay in your camps and be patient [Stay at home if you can, physically isolate and be patient]

The government urged patience: patience on the part of those at home who had been without loved ones in some cases for four years; patience on the part of farmers and other employers who had been short staffed for years; and, mostly patience on the part of our troops who had served so well, for so long and often under indescribable conditions.

To sustain morale, overcome boredom and prepare the veterans for post-war life, while in the demobilization camps the Canadians were encouraged to participate in physical training programs, organized sports and other recreational activities. They were also encouraged to participate in “Khaki University” an education program that offered elementary to university level education to idle troops. At least 50,000 Canadians took part in this program.

Nonetheless, a lack of information and rumours that their demobilization had been cancelled or delayed in favour of others, contributed to confusion and anger and in some cases unrest at the camps. Between 1918 and 1919, there were thirteen incidents of unrest at Canadian demobilization camps. In one such incident in March 1919, five soldiers were killed and another 23 wounded. While violence occurred at the demobilization camps of other countries (including British camps), the British media focussed their reporting on the violence in the Canadian camps. It wasn’t fair—but it led to the British government increasing the rate of the return of the Canadians.

Suffice it to say, it was a long time before 50,000 people a month were being shipped from Britain to Canada as part of the demobilization efforts. At first the number was just 2,000 per month. By March 1919, 127,000 members of the force had returned home.

Quickly and With Relative Ease

By late summer, almost all Canadian forces in England had sailed home. Years later it was said: “Despite the disturbances, the demobilization process had moved quickly and with relative ease.” I suspect few said that at the time. Maybe ten years from now we will look back and say that “the program of securing and dispensing vaccines across the country proceeded quickly and with relative ease”. Not many would say that now.

Post script

One of the other things that struck me as I read about this period of time were the 37,000 Canadian dependents. Who were the women among that group? Were they British women that the Canadians met and married while stationed in England? Were they Canadian women who travelled to England to be nearer to their serving men? I asked my researcher Colleen Mahoney to look into this. Click here for more information about these women and what they faced as the travelled to and arrived in Canada.

To Pre-Order Your Copy of

The Mending

select one of these links.