ARTICLE 1: LESSONS FROM THE SPANISH FLU

Reading and writing about Spanish Flu in January, 2020, as Wuhan, and then Italy, and then Iran and other countries experienced COVID 19, was fascinating and, as is always the case when reading history, I soon saw that there were lessons to be learned from it.

For a bit of historical context, the Spanish Flu originated in the spring of 1918. It arrived in Canada in September 1918. While it was commonly thought to have been brought to Canada from troops returning from Europe, more recent theories suggest that it may have been brought to Canada either by American Christians attending a Eucharistic Congress in Victoriaville, Quebec or US troops at an infantry camp in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario or in Montreal, Quebec or in Sydney, Nova Scotia. However it arrived in the east, it made its way across the country as trains took our troops west.

Within a month of its September 29 arrival in Toronto, half of the city’s population had been infected. Schools closed after hundreds of teachers and thousands of students were absent due to infection. In mid-October, the city ordered the closure of theatres, movie halls, and other public places. One enterprise though was required to be open more often. As the cemeteries could not keep up with the burials, they were ordered to be opened on Sundays. Hotels were converted to hospital space, as was Burwash Hall at the University of Toronto, and a building on the Exhibition grounds.

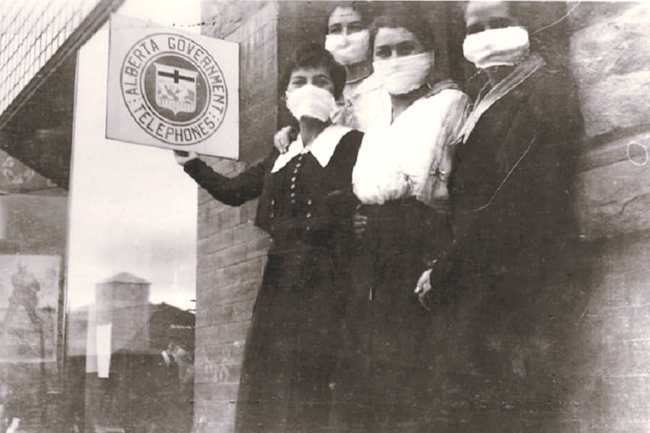

Canada had a good telephone system in 1918 but customers were dissuaded from using it that fall given the number of absent operators. Bell Telephone Co. urged users to limit their calls to emergencies only.

At the same time, towns and cities were urged to create a volunteer force of educated young women, like those pictured below, trained to supply nursing assistance wherever needed. They were to be known as Sisters of Service. In the Toronto area, the women were trained in the legislative building at Queen’s Park.

There was no vaccine for Spanish Flu. Tips to avoid contracting it included:

- Keeping one’s rooms well ventilated and at a consistent temperature of 65 – 72F

- Changing and boiling handkerchiefs frequently

- Eating plain nourishing food

- Keeping one’s feet dry and warm

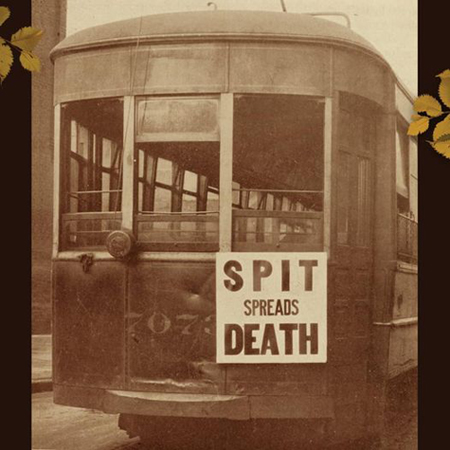

- Not expectorating (spitting) in public places

Once the flu was contracted, patients were urged to go to bed in a well ventilated room and to keep warm. Every patient was to have their own dishes, cutlery, basins and towels.

Brampton, being 45 kilometers northwest of Toronto, was just a step behind Toronto in experiencing the Spanish Flu. On October 17, 1918, W. D. Sharp, Brampton’s medical officer of health, ordered the closure of all schools, churches, and other places of “meeting or amusement.” The only exception to this was for wartime fundraising. The thinking was, I suppose, that if our boys could be putting their lives at risk at the front, we could do so at home if the purpose was to raise the funds required to support them. All citizens were urged to attend these rallies and to ‘come across with the cash to help hasten the crash’—the defeat of the Central powers, thought to be imminent.

In contrast with the COVID 19 response, Brampton businesses were not closed during this period, although some reduced their hours of operation. However, townspeople were not to visit or entertain others. Persons suffering from colds, sore throats, and coughs were to be avoided. Children were not to attend any gathering if they had a cough.

By October 30, 1918, the epidemic was deemed to be abating in Toronto. The day before, only 33 patients were admitted to hospital. A week before, twice that number died on a single day. It was predicted that the virus would disappear in Toronto the first week of November.

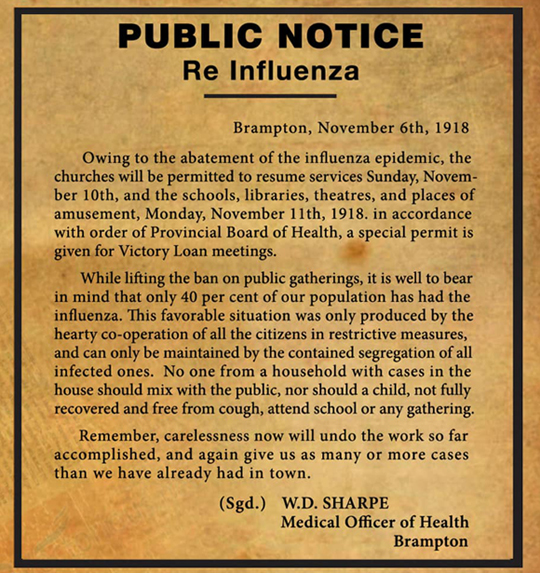

In early November, Brampton’s medical officer of health came to the same conclusion. He issued a notice stating that the town could resume church services Sunday, November 10, and that schools, libraries, theatres, and places of amusement could reopen Monday, November 11.

Of course, the streets themselves were the places of amusement on that day, and the opening of the schools was postponed for a further 24 hours as the Armistice was celebrated in one impromptu celebration after another. Though the ban on public gatherings was lifted in Brampton, segregation continued to be required for those who were infected or who lived in a household with infected members. To that point, only 40% of the town’s population had contracted the flu. Everyone was urged to avoid undoing the work so far accomplished.

The prognostications that the Spanish Flu would disappear from Toronto by early November and from Brampton a week later were incorrect but while the flu would rear its ugly head in the winters of 1919-1920 and 1920-1921, it was never as lethal as it was in the fall of 1918. There was never a second shut down of schools and places of public gatherings in Toronto or Brampton, although there was one in Hamilton in 1919.

However, the H1N1 strain that caused the Spanish Flu never really went away, it merely receded into the background, re-emerging as the regular seasonal flu. Occasionally, direct descendants of the Spanish Flu combined with bird flu or swine flu to create powerful new pandemic strains, such as what occurred in 1957, 1968 and 2009 each of which claimed millions of lives. Scientists claim that every strain of influenza A that has emerged since 1918 is derived from the Spanish flu.

In North American, the Spanish Flu took its highest toll on the very generation that had sacrificed so much to the just completed World War and more often, men than women. The explanation for the generational distinction relates to flus that existed before this generation was born. Those born after 1889 had never been exposed to a strain of flu similar to the Spanish Flu. They were more vulnerable to it that those born before that year and who had been exposed to it.

In one study of “excess” deaths of those between the ages of 15 and 50, during the fall of 1918, mortality rates were found to be 20-80% higher among men than women. There are two theories for this. The first is that men, being out in the community, were more likely to be exposed to the flu than women who stayed at home. Were it not for the war, I am not sure that this theory would hold much water. Men tend to return home to women for care when they are sick. However the second theory, helps bolster the first. It relates to the poorer health condition and general situation of men during this period. Many North American men in this generation were still living in crowded military camps or were with large groups of men in the process of returning home. Many were in hospitals. Certainly the flu took a higher toll on those in poor health, those suffering with tuberculosis or other chest ailments and those who were infirm. These of course were more often men than women.

The Spanish Flu of 1918 -1920 is said to have claimed the lives of 50,000 Canadians, just 10,000 less than the 60,000 Canadian lives lost in the maw of the Great War—a great toll for a country of just under 8,000,000 people.

To Pre-Order Your Copy of

The Mending

select one of these links.