“You need to add a chapter about Spanish flu,” my editor, Allister Thompson, told me after reading the entire 900,000-word manuscript for my book, Beneath the Alders. It was one of about ten substantive suggestions he made to me nearly five years ago. Mustering all of my amateur writing eloquence, I sent him a lengthy email disputing the validity of every suggestion. He complimented me on my reasoning, without raising a single rebuttal; without mentioning the over twenty years of experience he had in the publishing industry. Within a month, and without another word from him on the subject, I began to rewrite the manuscript to incorporate nine of his recommendations. Among other things, the manuscript for a single book would become, as he suggested, a manuscript for a three-book series. The only suggestion I did not accept related to the Spanish flu.

“I don’t have any content,” I said. The Beneath the Alders series is inspired by the life of my great-aunt, Jessie Roberts Current, told to me after she celebrated her hundredth birthday. My aunt had a remarkable life, due in large part to her experiences growing up in Brampton, Ontario in the first decades of the 20th century. Two of her uncles were town mayors, and her father led a number of public works. Her brother was a member of the Brampton Excelsiors lacrosse team that vied for the Mann Cup in Vancouver in 1914, just months before the commencement of the Great War. Her father, her brother, and every one of her male cousins enlisted. She was an early farmerette helping to ease the Canadian wartime food shortage. She studied science at Victoria College and, given the insufficiency of marriageable men, went on to become a researcher, professor, and eventually a University of Toronto dean. Add to this a number of family secrets, foibles, and prejudices, and you get a story of life in small-town Canada, different from Canadian life a century later.

“But no one in her family died of Spanish flu,” I argued. I wasn’t even sure any of them had it. According to Perkins Bull, a local renaissance man if ever there was one—lawyer, businessman, property owner and historian—only 50 people in Peel County succumbed to the scourge. I wasn’t sure it was that big a thing.

“You’d better check,” Allister said. I reluctantly agreed to do so, once it was time to complete The Mending, the third book in the series. This January, returning to the Brampton library and reading the microfilm of the Conservator, the local paper of the time, I gained new insights. Combining them with the findings of Colleen Mahoney, my researcher, I realized that Allister was right (again!). The Spanish flu was a big thing. Reading about it in January 2020, as Wuhan, and then Italy, and then Iran and other countries experienced COVID 19, I realized, in fact, that it was fascinating and, as is always the case with history, there were lessons to be learned from it.

For a bit of historical context, the Spanish flu, which originated in Europe in the spring of 1918, arrived in Canada in September 1918, allegedly brought to Quebec City by a group of US soldiers. It reached Montreal and Toronto later that month and then made its way west as trains took our troops home.

Within a month of its September 29 arrival in Toronto, half of the city’s population had been infected. Schools closed after hundreds of teachers and thousands of students were absent due to infection. In mid-October, the city ordered the closure of theatres, movie halls, and other public places. One enterprise, though, was ordered to be open more often. As the cemeteries could not keep up with the burials, they were ordered to be opened on Sundays. Hotels were converted to hospital space, as was Burwash Hall at U of T, and a building on the Exhibition grounds.

Brampton, being 30 miles northwest of Toronto, was just a step behind Toronto in its experiences. On October 17, the medical officer of health ordered the closure of all schools, churches, and other places of “meeting or amusement.” The only exception to this was for wartime fundraising. The thinking was, I suppose, that if our boys could be putting their lives at risk at the front, we could do so at home if the purpose was to raise the funds required to support them.* All citizens were urged to attend these rallies and to ‘come across with the cash to help hasten the crash’—the defeat of the Central powers, thought to be imminent.

In contrast with today’s pandemic approach, Brampton businesses were not closed during this period, although some reduced their hours of operation. However, townspeople were not to visit or entertain others. Persons suffering from colds, sore throats, and coughs were to be avoided.

By October 30, the epidemic was deemed to be abating in Toronto. The day before, only 33 patients were admitted to hospital. A week before, twice that number died on a single day. It was predicted that the virus would disappear in Toronto the first week of November.

In early November, Brampton’s medical officer of health came to the same conclusion. He issued a notice stating that the town could resume church services Sunday, November 10, and that schools, libraries, theatres, and places of amusement could reopen Monday, November 11. Of course, the streets themselves were the places of amusement on that day, and the opening of the schools was postponed for a further 24 hours as the Armistice was celebrated in one impromptu celebration after another.

Though the ban on public gatherings was lifted in Brampton, segregation continued to be required for those who were infected or who lived in a household with infected members. To that point, only 40% of the town’s population had contracted the flu. Everyone was urged to avoid undoing the work so far accomplished.

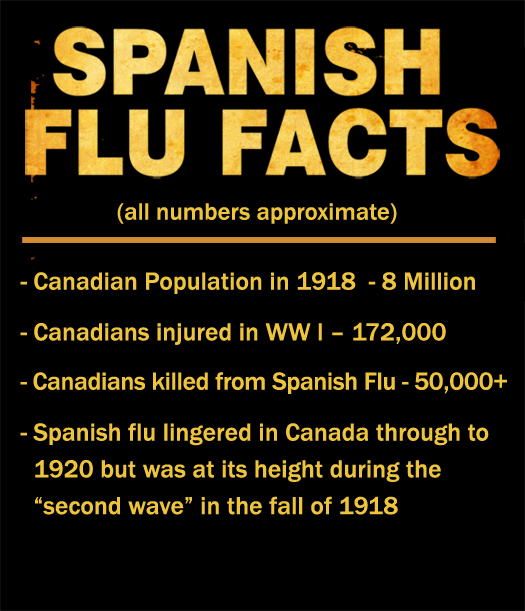

The prognostications that the flu would disappear from Toronto by early November and from Brampton a week later were incorrect. The virus continued its stealth-like attacks throughout the fall and into the spring of 1919. By the time it expired, it had claimed the lives of 50,000 Canadians, just 10,000 less than the 60,000 Canadian lives lost in the maw of the Great War—a great toll for a country of just under 8 million people. As the chief demographic for each type of decimation was those between the ages of 20 and 40, the flu exacerbated the ravage of a generation.

Lynne Golding is the best-selling author of The Beleaguered (2019), the second book in the Beneath the Alders Series, published by Blue Moon Publishers. Preceded by The Innocent (2018), the final book in the series, The Mending, is due to be in the spring of 2021. By day, Lynne is a senior partner in the law firm Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP, where she leads their health law group.

* Conservator, October 24, 1918